Matmos are masters of the electronic concept album, and I was delighted that the archive in question is the plethora of “sound” albums released by the maverick founder of Folkways, Moses Asch. Beyond the concept, these glitchy, rhythmic, noisy, textural pieces are a joy to listen to and behold.

Matmos are researchers of the highest order

A good chunk of my daylight hours are spent at my daylight job, where I work as a copy cataloger for the public library. In the catalog department we have the fun job of giving all the new books, CD’s, vinyl albums, audio books and other materials, their call numbers, so our patrons can track them down on the shelves. We also make sure they have the right subject headings, summaries, and other information that will make it easy for the researcher to find what they are looking for they are looking for. I was very excited that our library picked up the new Matmos album and even more excited that it had as a subject matter, the idea of the archive. Matmos are masters of the electronic concept album, and I was delighted that the archive in question is the plethora of “sound” albums released by the maverick founder of Folkways, Moses Asch. Beyond the concept, these glitchy, rhythmic, noisy, textural pieces are a joy to listen to and behold.

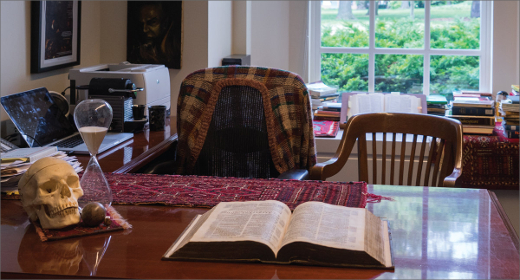

I got so excited about this album I got into a chat with our resident data librarian about the relationship between archives and libraries. She had just returned from a conference on this subject and I showed her the CD. She had herself worked in an archive before coming to the library, and I was given the rundown on the subtle differences between the two. Without getting into the weeds too much, libraries focus on circulating their material for the most part and everything they acquire is with the goal of getting it into the hands of the community, contributing to culture and the life of the mind. Archives specialize in collecting and preserving unique and rare materials, often for scholars doing research, and for historical documentation.

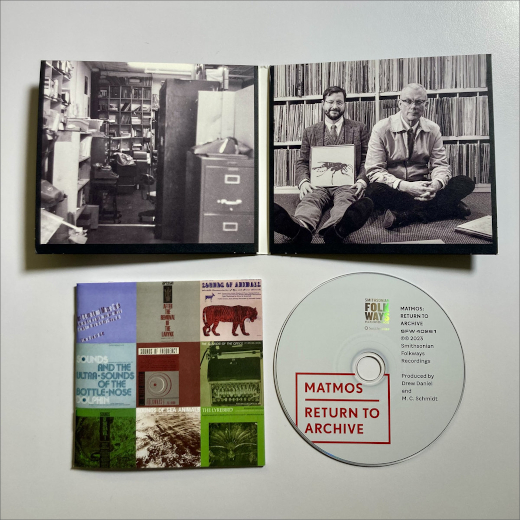

There is no question that Matmos are researchers of the highest order. What they have produced here is a sonic dissertation, though a written one would well be within their orbit of activity, and the extensive liner notes make a treatise that is both pleasurable and edifying. This is the kind of creative work archives and libraries are made for, where artists in whatever media (or intermedia) are able to come in and synthesize something new from the plethora of preserved materials.

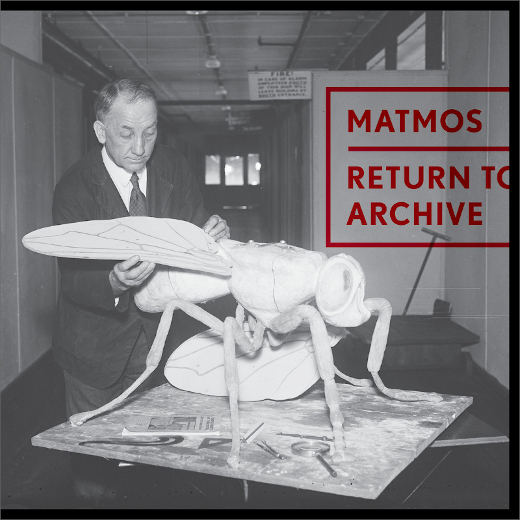

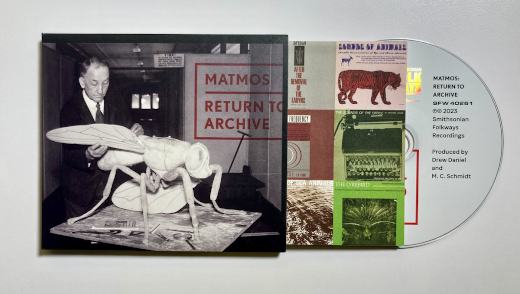

Moe Asch certainly bequeathed a plethora of materials to humanity from his activity as a collector of vast ranges of sound and music. He had first captured the imaginations of listeners with his Disc and Asch labels, devoted to the dissemination of jazz and folk music. He made considerable expansions upon these offerings when he started Folkways in 1948. Asch was interested in recording sound as well as song and music. He ended up releasing 2,168 titles on his label and these included such famous slabs of wax as Sounds of North American Frogs (a favorite for biologists and those with discerning ears) and Vox Humana: Alfred Wolfsohn’s Experiments in Extension of Human Vocal Range (Stockhausen would have approved), and on to The Voices of the Satellites and The International Morse Code: A Teaching Record Using the Audio-Vis-Tac Method. Beyond this were recordings of offices, of children’s camps, and many, many more field recordings of animals. This is the type of material from Folkways that Matmos set out to sample when they returned to the archive.

Musical ethnography ::

Asch was a true archivist. Unlike other record labels he wanted to keep the albums he put out in print, preserve them for the future, even if they weren’t big sellers. He famously said of his catalog, “just because the letter J is less popular than the letter S, you don’t take it out of the dictionary.” He made it a part of his mission to never delete a single title of anything that he issued, ever. The Smithsonian Institute acquired the Folkways catalog just before the death of Asch with his cooperation and that of his family. The recordings he captured now continue to ring out, and importantly as in this album, provide source material for new amalgamations. For M.C. Schmidt and Drew Daniel sampling is a way of life, though they can be just as happy with traditional synths as they showed on their album Supreme Balloon. For this outing they romp their way through Asch’s legacy, leaving behind a prodigious reorganization, regenerating the material, giving it new life.

Musical ethnography could also be considered a way of life for Drew Daniel. In his alter ego as The Soft Pink Truth he has translated the scalding sounds of black metal into the profanations heard on the album Why Do the Heathen Rage? where he transposed the riff of classic true KVLT tracks from Venom and Darkthrone into techno fit for the clubs. The album is gleeful in the way that it mixes two diametrically opposed subcultures together but it can also be heard as a true appreciation of the aesthetics of both. He does something similar on The Soft Pink Truth’s Am I Free to Go? where the anarchist politics of crust punk become grist for a mixing of styles, again showing his affection for both. Yet like an ethnographer, Daniel seems to retain a certain amount of emotional distance from black metal and crust punk as he goes about slightly poking fun at both all while memorializing these subcultures in a techno tribute. These kind of activities recall those of Harry Everett Smith, the archivist, collagist, collector, anthropologist, painter and film maker who had his own love affairs with jazz, folk, Native American music, and sacred harp singing, also known as shape note singing.

The first track “Good Morning Electronics” uses jump-cuts to plunder its way through the plethora of the material available to them as they jump straight into the archive. It’s more of a pure cut-up, though cleanly moving from one sound to the next, and can be heard as an introductory statement to all that comes next. “Injection Basic Sound” has fast-paced click cuts, with a number of strange vocalizations layered over top, and will appeal to fans of their rhythmic beats. “Mud Dauber Wasp” moves into the territory of noise and recalls the balloon sounds used on their album Quasi-Objects. The sound is aggressive, perhaps like the wasps themselves, which are heard in the background above a pulsing gabber line, with layers of schwobbly electro percolations.

“Music or Noise?” asks the question that many people have been asking since the days of Edgard Varèse and Luigi Russolo. There is certainly no escape from noise, or the question if particular pieces of art are music or babel of pandemonium. People are still asking the question. The “Mud Dauber Wasp” track was noisier than this one, to my ears. This track has Asian sounding strings being plucked, people screaming, singing, and on into other sounds that became disorienting because the sound mosaic is made up of so many small fragmented pieces. All of the details reveal added layers of intricacy on repeated listening. The next question asked is “Why?” No answer is given. But there are plenty of voices, animal and human, melded together into a surrealistic collage.

“Lend me your ears” starts with that phrase being played at different pitches accompanied by piano, whistling or scraping, abstract beats, and a rhythmic sound that can best be described as gloop. Or what ambient master Robert Rich has called glurp, a kind of liquid and organic sounding texture. It is like you can hear the process of compost being made inside the song, the samples all decomposing, but as they do, becoming ever more fertile.

Transforming from one sound to the next ::

Each of the pieces moves with speed and velocity, transforming from one sound to the next until the title track is reached. This thirteen-minute head cleaner begins with sonorous industrial drones of machinery and the plinking of guns. Or so it sounds. It’s hard to know exactly which sounds are which. That makes this kind of music perfect for imaginary voyages. Yet, for those who do want to know the extensive liner notes tell where the sounds are sourced from, but these are best left, in my opinion, to read, until the album has been listened to a few times first, so the mystery of the sources can be allowed to unfold. This track could have easily been something created at the GRMC studios in the early days of musique concrète, just as it might have been something Steve Stapleton would have put on an early Nurse With Wound record. Of course it also sounds like a Matmos record at their most abstract. Whistlers or fireworks, more organic glurpity-glurp, and the ring of a doorbell over pitch shifted voices come in at the end, making it sound like you are emerging from a deep dream.

Or maybe it’s a matter of going into a deep dream. After one more track with the insect clicks of Japanese beetles, the final track emerges, “Going to Sleep.” This samples the kind of material you might find combing through old tapes at a thrift store, hypnosis tapes, or slow regressions used to help you relax. Only they are interspersed with disturbing sounds that would wake you from any kind of hypnagogia. At last it does drift into about as close to lullaby-mode as Matmos might get on this album, with sounds from what sound like Geiger counters, and other instruments, as well as the dust and grit of vinyl.

Smithsonian Folkways gave the duo permission to plunder and reuse the recordings, but it seems like it might not hardly matter if they did. Moe Asch released Harry Everett Smith’s monumental documentation of commercial recordings which has a vastly influential Anthology of American Folk Music. The work was essentially a bootleg even if many of the 78s that Smith had assembled his anthology had long been out of print. Smith’s notes in the booklet that accompanied the anthology pointed to a philosophical position on the creative reuse of existing works. He quoted the judicial philosopher and jurist Learned Hand, who noted that “If by some magic a man who had never known it were to compose a new Keats’ Ode on a Grecian Urn, he would be an author, and if he copyrighted it, others might not copy that poem, though they might of course copy Keats.”

Asch had written that “There is a provision in the copyright law, that says people have the right to know… Actually, it came out of the policy on automobiles… If a manufacturer stopped making a certain part of a car his whole factory could be thrown into the public domain. Car owners had a right to those parts. We applied the same logic to these records that were no longer available.”

Matmos was invited into the archive to celebrate the 75th anniversary of Folkways in 2023. But even if they hadn’t been invited and they did this on their own gumption, the end result would have been so transformed it might not have made an appreciable difference about where the sounds came from. They agreed to the commission of coming in to sample the archive, but with the caveat that they wouldn’t incorporate any original music into the album. The end result remains highly original.

Now that Matmos have tackled the part of the archive dedicated to the “so called non-musical” sound albums on Folkways, it would be great to see them manifest an album riffing off the material from Harry Everett Smith’s famous anthology, giving it their studied and nuanced treatment. The centennial of Smith’s birth was also in 2023, and there is now the first full length biography on the American original, penned by none other than John Szwed, who has previously written biographies of Sun Ra and Alan Lomax. His Cosmic Scholar: The Life and Times of Harry Smith makes a perfect accompaniment to Matmos’ ride through just one small segment of Asch’s collection. If I had my druthers, it would be my wish to see Matmos return to archive again, and plunder Smith’s anthology for a future installment.

Return to Archive is available on Smithsonian Folkways Recordings. [Bandcamp | Site]

![Pole :: Tempus Remixes (Mute) — [concise]](https://igloomag.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/pole-tempus-remixes_feat-75x75.jpg)

![Hasbeen :: Bunker Symphonies II (Clean Error) — [concise]](https://igloomag.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/hasbeen-bunker-symphonies-ii_feat-75x75.jpg)