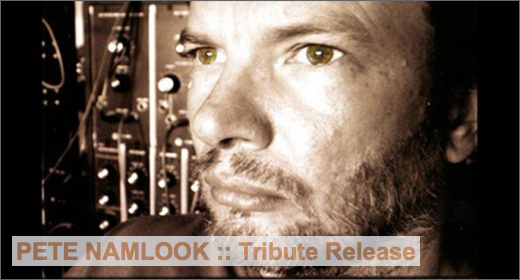

This tribute is for Pete Namlook. To honor his memory, I brought together several artists who had worked with him or released music on his label. It has been an intense labor of love spanning nearly two years, and I am profoundly grateful to everyone who contributed their sounds, their hearts, and their spirit to this project. ~Lorenzo Montanà

Unexplored soundscapes

Lorenzo Montanà’s Return to the Labyrinth is a tribute to Pete Namlook. In Lorenzo’s own words, “The passing of Pete was a heartfelt loss for me and for the entire electronic music community and beyond. His immense contributions to music and his boundless creativity continue to resonate deeply in our hearts and echo in our ears. We collaborated on five albums for the Labyrinth series, driven by an endless passion and enthusiasm. He was eager to carry on with this series, which had been inspiring him so profoundly. Before he left us, Pete shared a dream of coming to Italy to work in my studio, a dream that, sadly, was never realized.”

Mirco Salvadori (Igloo) :: Pete Namlook—a name that meant so much to us, tireless chart-makers of routes that were little known at the time. Who was Pete, and how did a young Italian sound artist come into contact with someone who was already a guru of the new electronic sound?

Lorenzo Montanà :: I was introduced to Pete Namlook’s music through a few late-night broadcasts of local radio stations that explored ambient sounds, which were still relatively unknown at the time, and via the most underground record stores in Bologna, such as the iconic Disco D’Oro and Underground. There, Pete was an institution; his name evoked unexplored soundscapes and a radically free musical vision.

After years of experimenting with electronics, I was working on the production of Tying Tiffany’s second album. We had already involved Wolfgang Schroedl from Liquido and Nic Endo from Atari Teenage Riot on the record, and we had even performed some shows together. So, with a touch of madness, we decided to aim high and try to contact Pete, driven by the idea of closing the album with a more expansive and atmospheric track.

A couple of weeks later, his response arrived: the project intrigued him. Not only did he accept, but he also sent us his track, perfectly in tune with the song. It was an incredible moment. That collaboration not only found a place in the album but was also released as part of his project Air V – Jeux Dangereux (Silent State Recordings, 2006.

Shortly afterward, during our tour in Germany, France, and Luxembourg, which was only a few kilometers from his home, he himself suggested that we visit him. When we landed, he picked us up at the airport in a gorgeous red 60s Triumph convertible, an image that seemed straight out of another era. On his wrist, he wore his unmistakable bracelet with the FAX logo, like a seal of his musical universe.

Stepping into his studio, nestled in the serenity of the Black Forest, felt like entering a sanctuary of sound. He welcomed us in his unmistakable style, offering us a cup of tea while we talked about his passions: science fiction, botany, music. Around us, analog synths coexisted with spaceship prototypes, Star Wars collections, rare instruments, and model tree miniatures. At that time, besides music, he was enthusiastically dedicated to beekeeping and tending to his garden. He even offered us the honey he produced himself, saying he understood more about himself and the essence of sound by observing how nature acts and evolves.

That meeting left a profound mark. When I returned home, I felt the need to share something of mine with him. I sent him some solo tracks, hoping they might intrigue him. After some time, his response arrived: he found my music interesting but wasn’t sure if it fit the FAX label. He would think about it. Weeks of waiting passed until one day I received his email: he wanted to release it. He liked the idea of introducing something slightly different from the usual label catalog. And so, my first solo album Black Ivy saw the light on FAX, the label I had always admired the most in the electronic music scene.

Sonic dialogue ::

Igloo :: Let’s get straight to the point: the Labyrinth project. Five volumes, each more intense than the last, spanning five years from 2010 to 2015. Take us back and tell us how it all happened.

Lorenzo Montanà :: After my debut on FAX, the first positive feedback started coming in, both from the press and from the label’s most attentive listeners. Shortly afterward, it was Pete himself who expressed the desire to collaborate with me and try to create something together. I had just debuted with my first album, and suddenly, I found myself working side by side with the Master. It left me speechless.

I didn’t waste time, I seized the opportunity to pour my entire musical universe into this collaboration. We began exchanging ideas: I would send him my tracks, and within a few days, he would return the finished work. He said he was intrigued by my production style and had a lot of fun working on it. Our sonic dialogue developed naturally, without effort, and at an astonishing speed.

One day, he asked me for advice on what to name the project. Without hesitation, I suggested Labyrinth. To me, that name evoked a 1990s radio show, Il Labirinto, curated by Steeve on Radio Italia Network. That broadcast had been fundamental in my journey, it had opened the doors to the ambient and electronic universe, introducing me to, among others, Pete’s immense music. It was a thread being tied back together over time. Ironically, by the late ’90s, I found myself working at that very radio station, handling editing and directing for some programs. Pete immediately found the name perfect, and thus, the first volume of Labyrinth was born.

“His enthusiasm was contagious, he immersed himself in the project so deeply that he even expressed a desire to observe my work in my own studio, with my plug-ins. It seemed incredible to me: with all the equipment at his disposal, he was curious to see my creative process.” ~Lorenzo Montanà

But that was just the beginning. The first album led to the second, then the third… the creative flow seemed unstoppable. After the first two volumes, I decided to visit him in his studio, and there we recorded some tracks together for Labyrinth III and Labyrinth IV. His enthusiasm was contagious, he immersed himself in the project so deeply that he even expressed a desire to observe my work in my own studio, with my plug-ins. It seemed incredible to me: with all the equipment at his disposal, he was curious to see my creative process.

Unfortunately, he told me he had difficulty focusing on work during the summer, so we decided to wait until autumn. But that meeting in my studio never happened. Pete left us before we could make it a reality. It was his daughter, Fabia, who called me in the middle of the night to deliver the terrible news. Labyrinth 5 is not only the end of our series, but also the last album he worked on before leaving us.

Igloo :: Let’s open a technical parenthesis, personally, I don’t see it as primary, but I know it’s fundamental for those who produce electronic sound: what was the creative process of the project, and what instruments and techniques did you use to create that auditory immersion? Keep in mind that as I write these questions, I’m fully immersed in Labyrinth 5 with Path XXXII, just so you know.

Lorenzo Montanà :: The creative process was always guided by instinct, without predefined schemes. In the studio, Pete had an endless arsenal of instruments: rare synthesizers, analog modules, and all kinds of software sounds. The first time I went to record with him, I remember he asked me which software I used for production. I answered, Cubase. Without saying a word, he got up, left the room, and after a few minutes, returned with exactly the same version of Cubase that I used. He casually told me he had all the software, he collected them, tested them, and often collaborated with software companies to improve them.

His knowledge of instruments was immense. In his studio, there were legendary synths that I had only seen as plug-ins or in old photos, and I could finally see him working with those incredible machines. I was fascinated when I saw him tuning an Oberheim 4 Voice using a simple guitar tuner, I had never seen anyone do it that way. But the biggest surprise came when he picked up an electric guitar and, with absolute ease, started improvising a jazz solo. His touch was refined, his taste incredible. At that moment, I realized that Pete wasn’t just a pioneer of electronic music, he was a complete musician, with a skill set far beyond the realm of synthesizers.

Igloo :: What drove you in the search for a new ambient expressionism, if I may use the term? What were you looking for?

Lorenzo Montanà :: I’ve always experienced music, and ambient in particular, as a blank canvas, an infinite space where I can paint shapes, colors, and tones without constraints. Unlike other genres, ambient allows for absolute expressive freedom: one can choose to follow a rhythm or dissolve into an abstract world, free of reference points, carried by pure sonic flow.

Pete was a natural extension of this vision, the perfect musical partner. His approach was as free as it was profound. With Labyrinth, we wanted to explore what you call an ambient expressionism that was not just pure sonic texture but had a strong evocative power, tracks capable of transporting the listener on an inner journey. For us, melody wasn’t secondary; it was a key to unlocking doors in the listener’s mind. Each track was conceived as a mental path, a journey through different states of consciousness, leading beyond the labyrinth.

Igloo :: One thing I’ve always wondered: what were Namlook’s musical influences, were there any artists he was particularly attached to? What are yours and how did you manage to reconcile the two experiences?

Lorenzo Montanà :: From what I got to know of him, his musical influences were broad and cross-disciplinary, and it’s hard to pinpoint a precise boundary. Certainly, some of the most important names for him were Klaus Schulze, with whom he collaborated on the The Dark Side of the Moog series, as well as legendary figures like Oskar Sala, Kraftwerk, and the KLF. But his inspiration went far beyond that: jazz, krautrock, and progressive rock were as much a part of his musical universe as more experimental electronics.

One thing that struck me deeply was his way of perceiving music as a direct reflection of nature. In a beautiful documentary made about him during the recordings of Labyrinth, produced by Telekom Electronic Beats TV, he talked about how he loved observing nature evolve, and how it helped shape his music and his view of life. He spoke of a green meadow, full of plants that seemed similar but each with its own uniqueness, movement, and character. This idea of diversity and ongoing transformation drove him to create and also to collaborate with artists from diverse backgrounds, allowing himself to be influenced by new sounds and never staying fixed in one style.

His approach to ambient music was very different from the idea of ambient as a mere sound carpet, which is often associated with Brian Eno. For him, ambient was a sonic adventure, a journey capable of generating intense and dynamic emotions. For this reason, his productions could range from ethnic sounds to electronic trance-inspired ones, as well as jazz or techno-ambient elements, depending on the project he was working on and the sonic identity he wanted to express.

My own musical journey has been one of exploring different genres and cultures, from new wave to electronic, with a particular attraction to ethnic music. Artists like Stephan Micus, Tom Jobim, Erik Satie, Cesária Évora, and Thomas Newman have left a significant mark on my artistic development. In this context, Pete was one of my main sources of inspiration, deeply influencing my approach to music.

His eclecticism, constant innovation, and fearlessness in experimenting made him unique. I also have a fairly broad musical background and loved discussing with him what had influenced him over time. I remember one day we listened to a track from his Air project with a strong exotica vibe, and I told him how much I loved the productions of Les Baxter, Arthur Lyman, and Yma Sumac. That sparked a long conversation about exotica and 1950s cocktail jazz, a genre I never imagined he would be interested in, but he found it fascinating. He was surprised that I knew and appreciated such forgotten genres, and at that moment I realized how rare it was to find such a deep connection with another musician. In fact, a few years later, I released an album called ISO LE, inspired by jazz exotica mixed with electronic ambient, much like he did in his AIR series.

The intersection of our musical experiences was incredible: on one hand, he had his broad and ever-evolving vision, while on the other, I had a more melodic and cinematic approach, focused on sound design. But this contrast led to something unique. With Labyrinth, we found the perfect balance, a dialogue between two worlds that influenced each other to explore new sonic territories.

Igloo :: Return to the Labyrinth: the news of the release of a new chapter after thirteen years literally surprised me, a surprise that grew exponentially when I read the names of those who contributed to its success, two in particular: High Intelligence Agency and Dr. Atmo, icons of a decidedly spacey era, for ambient electronic sound. As already asked in the second question: bring us to the present and tell us how it went.

Lorenzo Montanà :: Return to the Labyrinth arrives exactly 13 years after the last release in the Labyrinth series, a long period in which Pete Namlook‘s music continued to resonate in the soul of those who followed and loved him. In the meantime, shortly after his passing, a tribute titled Die Welt ist Klang was released, conceived by FAX‘s then-American distributor, EAR/Rational. This compilation featured many of the artists who had released music on the legendary label, and I was among them with an unreleased track: a demo for Labyrinth that had never been published.

The idea of bringing the series back to life came from the desire to keep alive that spirit of sonic exploration that characterized FAX. With the support of Dave from EAR/Rational, I sought to contact some of those artists to breathe new life into Labyrinth, respecting its essence but allowing each musician to express their own artistic identity. I thought the most natural thing would be to revive that philosophy of cross-pollination that Pete loved so much: one artist per track, with the aim of recreating those vast, enveloping sounds that made this series so special.

Expressive freedom without constraints ::

I didn’t expect such an enthusiastic response, especially from some of the historic names you mentioned. Seeing musicians who were part of that era eagerly accept the invitation to participate in the project was an incredible emotion. I knew it would be a sincere tribute, but I didn’t imagine it would garner so much attention and involvement.

In the end, Return to the Labyrinth is not just a new chapter in the series, but a true homage to Pete’s philosophy: to create music without boundaries, to allow different styles and sensibilities to communicate, to give space to expressive freedom without constraints. I am deeply grateful to all the artists who contributed with seriousness and passion, putting a piece of themselves into each track. And I’m sure Pete would have appreciated this celebration of his musical spirit.

Igloo :: What was the reaction of the eight sonic entities who accompanied you on this project, and at this point, who are they, just to stir the memory of those who have always considered FAX a label superior in every sense?

Lorenzo Montanà :: The eight extraordinary artists who accompanied me on this musical journey each represent, in their own way, the legacy and spirit of FAX. Starting with the legendary names, we have Bobby Bird, aka Higher Intelligence Agency, an English producer who, together with Pete, created one of my favorite series: S.H.A.D.O. Notably, his debut album Colourform (1993) is considered a landmark release in the British ambient scene, and his collaboration with Geir Jenssen (Biosphere) on Polar Sequences (1996) further showcased his innovative approach to ambient music. I had the pleasure of meeting him in Milan during one of his live sets, and it was incredible to collaborate with him on this project. Another legendary figure is Dr. Atmo, a prominent DJ from Frankfurt and a key contributor to the Silence series, renowned for its fusion of ethnic sounds and deeply evocative atmospheres. His musical sensitivity has left an indelible mark on FAX’s history, and involving him in this project was a great honor. His collaborations with artists like Pete Namlook and Oliver Lieb have significantly shaped the ambient music scene.

Then there’s Wolfram Spyra, a highly talented musician, capable of blending sophisticated electronic atmospheres with elements of jazz and fusion. For this occasion, he chose to play the guitar, a tribute to the way Pete himself often incorporated the sound of the six-string into the Labyrinth series, creating an even deeper connection with the original aesthetic of the project.

Among the collaborators, we also have André Ruello, aka Material Object, an extraordinary sound designer who worked with Pete on the Elektronik series. Not everyone knows that, in addition to being a great sound artist, André also created several covers for FAX, including the original Labyrinth cover, a detail that adds even more value to his contribution.

Adding a more rhythmic and organic touch is Gabriel Le Mar, an excellent musician and guitarist who brought his dub-tech style, which characterizes his productions and performances at international festivals. He has collaborated with Dr. Motte, another iconic figure and founder of the Berlin Loveparade, and his style brought a new sonic shade to the album.

From the new generation of artists connected to the FAX universe, there’s Mick Chillage, an Irish producer whose album Faxology redefined and reworked the most iconic sounds of the label. Together with Lee Norris, he formed the project Autumn of Communion, whose self-titled album became the final release of the FAX label in November 2012, following the untimely passing of Pete Namlook. We had already worked together on Deviazioni Cosmiche, Carpe Sonum) and his ability to create deep, immersive soundscapes made him a perfect fit for Return to the Labyrinth. His contribution on this track reminds me very much of Pete’s touch.

Completing the picture are Gate Zero, a German producer, is acclaimed for his meticulous crafting of atmospheric soundscapes intertwined with minimal rhythms, evoking introspective journeys through subtle melodies and intricate electronic textures. Krystian Shek brings his distinctive dub-ambient style, characterized by rich chromatic nuances and a fusion of traditional instruments with electronic elements, resulting in emotionally resonant compositions. Together, their contributions enrich the project with depth and diverse auditory experiences.The most fascinating thing was seeing how each artist interpreted the spirit of Labyrinth with their own sensitivity. Each track is a fragment of this great sonic legacy, and those who are familiar with FAX will recognize a familiar place in each of them.

Igloo :: With this new chapter, do you think you managed to maintain the original spirit of the project, and what do you think time has irreparably changed, even though listening to it feels like returning to the golden days of cosmic sound?

Lorenzo Montanà :: Yes, I believe I managed to maintain the original spirit of Labyrinth, because that kind of sonic journey was never tied to a specific era or technology, but to a way of feeling music, of exploring it with an open mind and without preset patterns. Time, in a way, hasn’t touched us. Those who immerse themselves in these sounds are not bound by temporal or spatial coordinates: they explore inner dimensions, traverse boundless landscapes, almost traveling for themselves.

“Time, in a way, hasn’t touched us. Those who immerse themselves in these sounds are not bound by temporal or spatial coordinates: they explore inner dimensions, traverse boundless landscapes, almost traveling for themselves.” ~Lorenzo Montanà

The spirit with which we immersed ourselves in this new chapter was the same as when we pressed the first key, when we made the first note resonate in Labyrinth I. The same curiosity, the same desire to be surprised and to discover ourselves, without worrying too much about where the sound would take us. It’s true, many things have changed: technology has evolved, the tools are different, and perhaps the world around us is more hectic, more saturated with stimuli. But in the studio, at the heart of creation, all of this stayed outside.

We didn’t want to confine the creative process with rigid expectations, nor chase nostalgia or faithfully reproduce the past. We simply let ourselves go with the flow, with the spontaneous dialogue between ideas, insights, and frequencies. It was a game, a ritual, a collective experiment among minds and hearts coming from that background, from that school of thought where every sound is an opening to the unknown.

And perhaps this is the most precious aspect of Return to the Labyrinth: the fact that it’s not just a tribute, nor an exercise in style, but the natural continuation of a journey that began a long time ago, with the same authenticity and the same desire to explore the invisible.

Igloo :: In the previous volumes, you titled the tracks with the word path, but in Return you used the word journey. This differentiation struck me, and I’ve given it my own interpretation. Let’s see if it aligns with yours.

Lorenzo Montanà :: Yes, this difference is intentional and carries significant meaning. In the previous volumes, the tracks were titled Path because they represented a journey, an exploration carried out side by side with Pete, with his vision and instinct always present to guide the way. Each path was a fragment of a larger journey, a road that branched within a sound universe we built together, step by step.

Now, with Return to the Labyrinth, I felt it was time to change the perspective. I didn’t want to use Path anymore because those paths had been drawn with him, and without his direct presence, it would have felt like appropriating something that belonged to both of us. But at the same time, I wanted to find a way to honor his philosophy, that unique way of creating and sharing music.

That’s how Journey came to be. No longer a traced path, but an open experience, a collective exploration where each artist contributed their own vision, just like in the records from FAX. A journey that’s not limited to memory but continues to expand, transform, and carry forward that spirit of exploration that Pete always embodied.

The journey is also a symbol of connection: I no longer walk alongside Pete, but his spirit is present in every note, just as it is in the artists who contributed to this chapter. Each of them brings with them a fragment of that sonic school of thought, that free and visionary approach he made possible. Journey is the celebration of this: not a nostalgic return, but a natural continuation of something that has never ceased to exist.

Igloo :: So with certainty, the reason that drove you back into the Labyrinth is the memory of Namlook, a figure who was essential to you both personally and musically, a tribute owed to a Master.

Lorenzo Montanà :: My return to the Labyrinth is a tribute to Pete, a fundamental figure both artistically and personally. With him, there was a deep connection, not just musically, but also personally. Working together was one of the most formative experiences of my life. We often kept in touch, exchanging ideas and reflections, and each conversation was enriching.

This new chapter of the Labyrinth is not just a continuation of that thought, but a way to honor his philosophy of music and life. It’s my homage to everything he taught me and to what he represents to me. Returning to the Labyrinth is an act of affection and gratitude for a mentor and friend who left an indelible mark.

Igloo :: In his first work titled “Silence,” created with Amir Abadi aka Dr. Atmo, there’s a track called “Garden of Dreams,” do you think it’s from that place that he’s now listening to your endless journey in his memory?

Lorenzo Montanà :: “Garden of Dreams” is a track that evokes deep and timeless sensations. When I listen to it, it transports me to a dimension where reality and imagination blend, and it’s beautiful to think that Pete, from that “garden of dreams,” is following our path, appreciating our efforts to keep his musical vision alive. Collaborating with him deeply enriched my artistic and human experience, and with this new chapter, I feel we’re continuing down the path we traced together, honoring his contribution to music.

Pete Namlook (born 25 November 1960 as Peter Kuhlmann [ˈkuːlmaːn] in Frankfurt, West Germany – 8 November 2012) was an ambient and electronic music producer and composer. In 1992, he founded the German record label FAX +49-69/450464, which he oversaw. He was inspired by the music of Eberhard Weber, Miles Davis, Antonio Carlos Jobim, Chopin, Wendy Carlos, Tangerine Dream, and Pink Floyd, and most importantly Klaus Schulze. Pete Namlook released many solo albums, as well as collaboration albums with notable artists such as Klaus Schulze, Bill Laswell, Geir Jenssen/Biosphere, Gaudi, Richie Hawtin, Tetsu Inoue, Uwe Schmidt (Atom™), Amir Abadi (Dr. Atmo), and David Moufang (Move D). By August 2005, Namlook and collaborators had released 135 albums (excluding re-releases, vinyl singles, compilations of existing material, and FAX releases beginning with PS, in which he personally was not involved in the music making). ~Wikipedia

Return to the Labyrinth is available on Bandcamp.

Mastering by Lorenzo Montanà, Artwork: LoMo