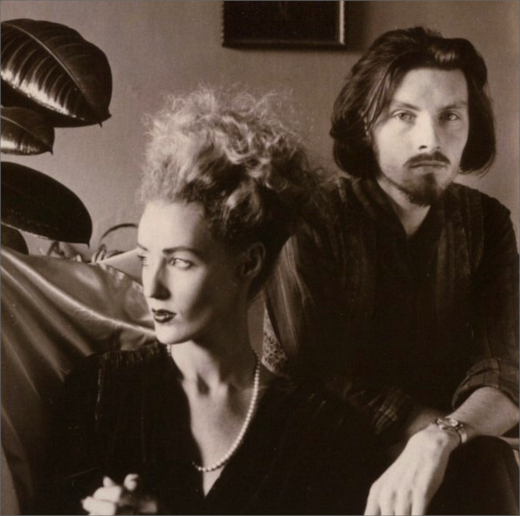

If her Dead Can Dance duo with Brendan Perry has given them a unique place in the musical landscape for almost 40 years, she has also conquered a new audience since her interpretation for the Gladiator movie. She reveals all the details about this universal language that has made her reputation.

Connecting with nature and connecting with the universe

“Otherworldly,” “mystical,” “touching the divine,” so many adjectives that come up frequently in an attempt to define the impressive voice of Lisa Gerrard. If her Dead Can Dance duo with Brendan Perry has given them a unique place in the musical landscape for almost 40 years, she has also conquered a new audience since her interpretation for the Gladiator movie. She reveals all the details about this universal language that has made her reputation.

Christopher Mathieu :: The success of Dead Can Dance across the 80’s & 90’s seems to have mostly spread through word of mouth. Are there any key moments in the career of the band which you think propelled it to a wider audience?

Lisa Gerrard :: Yes, there definitely are. One of the first ones was the film Baraka in 1992. I had a piece of music called “The Host Of Seraphim“ already existing and we were doing a concert in Los Angeles. Mark Magidson (one of the producers of Baraka) contacted me and said that he wanted to use this particular piece in the movie. I spoke to Brendan (Perry,) who said: “Yeah, that sounds interesting.” Then, Mark said to me: “Would you come to the studio and record another piece?” — which I did. It was over Auschwitz, a very sad area of this piece of work (Baraka is a contemplative documentary-style film without protagonists that shows various parts of the world often rich with historical content accompanied by a music soundtrack as its sole audio source.) So then, from that point, he said to me: “What do you want me to pay you for this work that you’ve done?“ And I thought: “Oh, I can’t charge to sing over Auschwitz, I mean, that’s just not going to be appropriate.“ So, I said: “Look, leave it, don’t worry, you can use this piece — “The Host Of Seraphim.” And he said: “Are you sure?“ And I said: “Yes, absolutely.” And we forgot about it.

About 12 months went by and Brendan and I had done an album called Into The Labyrinth. It had a piece of music on it called “Yulunga.” Mark contacted me and said: “I really love this piece! When are you in LA?”, and I said: “Well, actually, we’re going to be there in a few weeks.“ And he said: “Can you come? Can we meet?“ We did. And he said: “I’d love to cut a video together for this from some of the footage that we have left over from Baraka,” and I said to him: “Look, that would be wonderful, but at this stage in our process, it’s entirely impossible for us to afford to pay for that. I mean, we can’t engage in this exercise with you. Absolutely not.“ Because the footage he was using from Baraka was in 70mm. I mean, it was extremely expensive to make. And he said: “No, no, since you were so gracious, I’m going to do this for you for nothing.“ So anyway, he cut this beautiful video together, and that video ended up on National Geographic being played probably 6 times a day for 12 months, and that really opened people’s knowledge of Dead Can Dance, of us existing.

And the second thing was “The Ubiquitous Mr. Lovegrove“ (another song from the Into The Labyrinth album) which was being promoted by college radio in America and accidentally went into the charts and climbed up in the commercial charts in America, and everyone was absolutely astonished. It was just a little bit later, maybe about six months later or something. So everyone in America started to know about Dead Can Dance then. So, they were the two milestones that really broke our music into people’s lives. Because everybody else had to find us under stones. (laughs)

After Spiritchaser in 1996 and until today, you’ve become more and more involved in collaborations. How do you typically choose the projects you’re going to work on?

Look, I’m pretty open. I mean, unless it’s something that depicts sort of, the sales of, I don’t know, military tanks, or, you know, cruelty to animals and children, I don’t have too many hard and fast rules. I’m really curious to see what’s going to happen more than anything else. I find it exciting to work with people. And I don’t always judge the music itself, because when someone makes music, they come from a very deep sacred part of this whole. Regardless of whether it’s commercial music or not, I don’t believe that anyone can expose themselves to this work without, in some way, surrendering their material cynicism. And so, when you start to unlock with voice — I mean, I can contribute other instruments with my yangqins and also keyboards with strings and what have you, but usually people come to me because they want me to sing — I find that when I do this, there’s something integral within the work that belongs uniquely to that individual that composed this piece of work that they haven’t unlocked.

Do they usually have the instrumental already composed, and you build on top of that, or do they do it around your melodic theme?

It depends! It can be both. Sometimes I get a drone, and sometimes I get a fully blown piece of music, depending on who is sending the piece, so…

You create the vocal leads, but do you also compose the instrumentals?

I do. In my own work, yes, of course. Otherwise, it wouldn’t be mine. (laughs)

When you perform live, does the type of venue or its size alter the way in which you sing?

No, because when the lights go out, you could be anywhere. You’re in your own zone. So, whether it’s the Rising Sun Hotel in Richmond, or it’s, you know, a O2 (chain of gigantic concert halls across Europe), arenas with Hans (Zimmer,) it’s really not that different, to be honest.

To the best of your ability, can you describe what happens when you sing? Because it seems as though you’re accessing other parallel realms or something.

When I sing, it’s an emotional expression. I’m not accessing other realms. I’m expressing myself emotionally through sound and telling a story. But it’s not a practical story, it’s an abstract story that leads to a place that — I know this sounds a bit convoluted but I believe this is true — I believe it leads us to a place where people have a language that they own, that has nothing to do with the practical language that they were taught to speak in. But it’s a language that we’re born with, with sounds. Everyone in the entire world has an emotional language or emotional sounds that they make. And I’ve developed those into a full language.

“Everyone in the entire world has an emotional language or emotional sounds that they make. And I’ve developed those into a full language.” ~Lisa Gerrard

Would you consider that it’s some form of channeling?

Channeling? I don’t know, people have said that. I hear people say things like: “Oh, you know, I saw you channeling and I saw you this, I saw you that.“ I’m not really sure. I know that when I hear the music, something happens, and something gets unlocked. And if it’s channeling, where’s it channeling from? I find that a bit frightening. Why would I want to, sort of, I don’t know… It’s like “What are you channeling?” Do you know what I mean? I mean, I don’t know, I think the work is very pure, it’s very innocent, which is why people don’t feel threatened by this work, and I’ve experienced a lot of catharsis with the work, a lot of tears from people, where I believe that the tears are coming from a realization that this is communicating in a language that they already have. I feel that there’s an integrity to the work and there’s an innocence and a purity to the work. It doesn’t tell you how to think, it doesn’t tell you how to feel. It’s like a small key unlocking in a… essentiality. So, all the things of the world fall away when we sing, not just me. When we sing, and if we make our sounds, there is like a resonance of something that we connect with. It’s that we connect; human beings connect through this resonant sound. And in some way, it has an intimacy. There’s something very intimate about it.

Is there some form of universality that you purposefully try to achieve or is it something that just comes naturally?

No, it comes naturally. It does. It really does come naturally. When I was a child, I used to sing in my language. And well, I can’t say my language, our language that we weren’t taught to speak in. And so, for as long as I know, it’s always been there. And no one has come in the way of — well, I’ve had people sort of question, you know, “why?” But it’s… I can’t not do that. It’s not possible to not do. I mean, I could stop singing, but if I hear music, it’s automatic.

Have you heard of Marc Liblin who used to dream in another language since childhood until he realized, 25 years later, that it was an ancient language from an island in the Pacific. He went there and they were amazed to see that he spoke it.

No, I’ve never heard of that, but I don’t doubt it at all. I think that all these languages exist somehow inside of us. I believe that’s a different thing. I don’t think that that’s our abstract language, but I can see how… I mean, if you drift off… If say, for instance, sometimes I listen to the radio in Arabic, because I want to hear some Arabic music, or maybe Korean radio or something — I like listening to different radios so I can hear some different music — and I know I don’t understand what they’re saying, but when I don’t concentrate on what they’re saying, somehow I do. But without knowing what they’re saying. But in some way, there’s a connection that I almost understand.

That language you speak, is there a name for it?

Well, some people call it glossolalia, which I don’t think it’s…

How do you call it?

Well, I call it a soulful song form, you know, singing… I don’t have a name, I don’t, you know, that’s the one thing that. Once I start applying practical measures to these things, I’m afraid I might frighten the Graces away. Because the reason that it exists is by virtue of the fact that it exists outside of the practical.

But when you sing it, the words exist. So, I mean, is there a grammatical form?

There are different languages for different pieces of music. There are words that I sing that turn up in all of the music that I sing for some reason, I’m not really sure why they turn up.

Do they have a specific meaning to you, those words?

No, they don’t have a specific practical meaning, they have a meaning of… an abstract emotional meaning.

So, there’s no way you could literally translate these words into English?

No… No, no, no… That would be defeating the purpose.

Would you say that you have a connection to the divine?

I have a very close relationship with God. I believe. I consider God. I consider a creator. I consider a wonderful energy of love and universal energy. I consider this. My work is not religious. People have said it’s spiritual. I don’t believe it’s spiritual. I believe it’s very human and connects to the human tissue, the human fabric. I listen to music sometimes and I think it sounds awe-inspiring, but awe-inspiring is not spiritual. Not in my understanding. Spiritual, for me, is a quiet, sacred sanctum relationship with who and where we are in an existential sense, connecting with nature and connecting with the universe, connecting with God in prayer, or simply just by uniting with animalisms and creation itself. So that’s something separate from the singing, really.

This connection is therefore something you still pursue outside of performing, in your daily life.

Yes, of course.

So, do you think that by now you have learned secrets of the beyond that you can share?

Secrets of the beyond that I can share? Um… (pauses)

Maybe it’s a bit far-fetched.

No, no, I do have secrets of the beyond. But I don’t know if they absolutely… I mean, I remember when my father was dying, and he was waiting for my mother to come. He hadn’t been lucid at all for a very long time, and my mother went to buy some flowers, and she hadn’t left his side for nearly two years. And on this one day, he turned to me very clearly and said: “Where’s your mother?“ I couldn’t believe it. And I said: “She’ll be here really soon.” He said (takes a solemn tone): “You don’t understand, daughter. I need to go over there. They’re waiting for me to come now. And I’m making them wait.“ He was so lucid. “And I can’t go until I’ve said goodbye to your mother.“ I had no way of contacting her. And I thought I said: “It’ll be all right. She won’t be much longer.“ Because he was getting quite stressed. And then finally, he waited and waited, and it was like he was waiting to go. He knew he was going to this other place and there were people there that were waiting for him. But finally, my mother came, and he died a few minutes later, because he was able to say goodbye. So, he let go then.

I have a feeling that animals do that. Don’t you think?

Yeah! They do. They wait. I had a dog wait for me, Clancy, he waited. He died the day after I arrived home, but he waited. He wanted to say goodbye. But you know, they’re still there, because when I get out of the car, sometimes, when I come back from a long journey, I don’t see them, but I get this kind of thing in the corner of my eye where I can sort of see the animal, I get flashes of the dogs meeting me, you know? And it’s weird! And of my cats as well, I sometimes get little flashes of them around the house. Like they’re still there!

The departed live on in the memory of the living.

Yeah, but they’re just in another plane outside of the physical body. I have many stories about that. I lost a horse and I grieved deeply. I couldn’t work. I was so ill with grief. And that night, I was lying in bed, and I felt him breathing against my ear. So, I think he was trying to comfort me. So, there is definitely a spirit realm in my understanding, my own experience.

“There are different languages for different pieces of music. There are words that I sing that turn up in all of the music that I sing for some reason, I’m not really sure why they turn up.” ~Lisa Gerrard

So, you don’t have any tips from the beyond because of your frequent connections?

No, I don’t have any tips, I’m afraid. I’m so sorry. (laughs) I know, everybody thinks that I will… but I don’t.

It’s because it seems you can access some things that most people can’t.

I think we can, I think it’s just that we’re not allowed to, and our confidence is low.

Not allowed to?

Yeah, we’re not really permitted to and we suffer shyness. I work with singers, I have worked with singers in the past, and if I’m in a group and I’m starting to get them to unlock their soul voice, you know, their abstract voice, at first, I say “Who’d like to start?“ And no hands go up. And then, after about half an hour, you can’t stop them, and you have to say to some: “Do you mind if Jane has a turn?“ Because they’re all just… once it opens. And there’s tears, and it’s cathartic, and they start to cry, and it’s like, this sound comes from deep within the emotional belly. And it’s really — I think it’s really healthy for us to do this kind of singing.

I’ll try this evening.

Do! Just do it! It’s in there!

How do you feel about electronic artists who have been sampling snippets of your voice over the years? (Her voice has been sampled by artists as diverse as The Future Sound Of London, The Chemical Brothers, Fergie, Venetian Snares or Porcupine Tree among many others.)

I love this! And I’m so excited about this. I’m really sad when Brendan says no, because I really feel — and I mean this most sincerely — that once we’ve done the work, we really don’t own it anymore. And it always excites me when I see what other people can do with those things. Because that’s art! Now, how can art be wrong? It is just art itself. It’s an absolute. It can’t be right or it can’t be wrong. It’s art. It exists outside of those kinds of critiques, you know, and is a critique within itself. So, it lives in isolation. So, I don’t really see how you can say no. On what grounds… that you can say no? But sometimes, Brendan has a problem with this.

Did you enjoy that music in the way they used it?

Yeah, absolutely! I love it! I think it’s fantastic. It’s fascinating.

Can we expect a new Dead Can Dance album or tour?

Definitely not. I think Dead Can Dance is over now. It’s really finished now. I think this is it. We’ve done our season. And, you know, the last concerts, we were repeating the same pieces over and over again. And it’s like, unless we’re going to do something new, and it’s become incredibly difficult for Brendan.

But you did have a new album. (Dionysus came out in 2018.)

Yeah, but it was very much Brendan’s album. It wasn’t like an album that Brendan and I wrote together like the older ones, you know. He needed to go on another pathway, and I respect that, as an artist. But it’s sort of started to wean itself away from the kind of connection that we had together. But that’s a natural thing, that’s an organic thing and you can’t fight this. It’s just… It is what it is. It’s the process. It’s part of the evolution of the work.

Was the way you were working with him different from the way you work with other collaborators?

Yes. First of all, we lived in the same house, maybe for a year. We did nothing but the music. I mean, occasionally we went to a pub, you know, had something to eat outside, but really, it was just the music… And you have to remember that in the early days, we were living on a very low income, so the opportunity to go outside and socialize and things like that was very limited, because we didn’t have any funds, but which really was the best time for us to develop our work.

Were you living in Melbourne?

At that time, we were living in Melbourne, and then we lived in London for five years. On the Isle of Dogs, we used to call it. “L’Île Des Chiens“ (laughs) (the interview takes place in France.) So, it wasn’t very pretty but it served our purpose.

Do you have any forthcoming collaborations?

(in a facetious tone) I have lots of collaborations. I’m always collaborating. (more seriously) Well, I’m always working with Hans, of course, on and off, different projects… and Zbigniew Preisner, I’ve got something coming up with him, the Polish composer. Do you know Zbigniew Preisner? He worked with Francis Ford Coppola.

Yes, I think you did two albums with him.

Yes, I’ve done two albums with him.

So, there’s a third one coming?

Yes! I’m also collaborating with Simon Bowley who’s a man that is my engineer and does my vocal production. Who else am I working with? Oh, Daniel Johns? You know, the man from Silverchair. Do you know Daniel Johns?

Silverchair?! Wow, that takes me back! (Silverchair were a teenage Australian grunge rock trio heavily inspired by Nirvana who had outstanding success in their home country and distinguished international commercial success in the mid to late 1990s. They officially stopped in 2011.)

He’s a really close friend of mine, so we’re planning on doing some things together. So, that’s pretty much… you know, but there’s always things coming in. Oh, I was going to work with Philip Glass. I’m not sure what’s going to happen with that.

That would be fantastic.

Yea. So, we’ll see how that goes.

Are you open to current up-and-coming artists getting in touch?

Most important. Most! I work with a lot of people that no one’s ever heard of.

I’m pretty sure people are intimidated too.

No, no, no, let them get in touch! They can go to lisagerrard.com and get in touch with me. And the thing is, I do a lot for dance companies as well.

One last question: Artistically speaking, what are the goals that you have yet to fulfill?

(Pauses and thinks before answering) My goal, really, is to remain open to anything that comes in front of me and treat with reverence and respect and contribute to this in the best way I can. That’s pretty much it, really.

Interview by Christopher Mathieu on May 6th, 2023 in Nice, France

Introductory photo credit: Zbyszek Warzynski

Visit Dead Can Dance at deadcandance.com.

Dionysus is available on PIAS.

“Dead Can Dance is an Australian neoclassical darkwave band from Melbourne. Currently composed of Lisa Gerrard and Brendan Perry, the group formed in 1981. They relocated to London the following year.” ~Wikipedia

“Formed 1981 in Melbourne, Australia, Dead Can Dance, an eclectic musical entity, were one of the main proponents of the 4AD label throughout the 1980s and 1990s. Though the band split in 1998, they reformed briefly for a world tour in 2005. In winter 2011, they reunited once again to record a new album and completed a world tour promoting its release in 2012.” ~Discogs

![Luke’s Anger :: Ceiling Walker EP (Love Love) — [concise]](https://igloomag.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/lukes-anger-ceiling-walker-vinyl_feat-75x75.jpg)

![Ndorfik & madebyitself :: Solos EP (People Can Listen) — [concise]](https://igloomag.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/ndorfik-madebyitself-solos_feat-75x75.jpg)