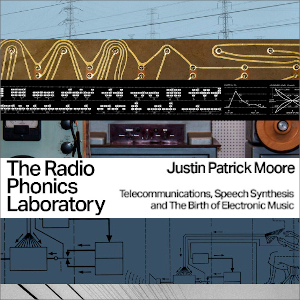

Material from the following interview with Don Slepian was used in Justin Patrick Moore’s new book The Radio Phonics Laboratory: Telecommunications, Speech Synthesis, and the Birth of Electronic Music from Velocity Press and available on Bookshop.org, Amazon, and fine bookstores everywhere.

Grounded in electronics

Material from the following interview with Don Slepian was used in Justin Patrick Moore’s new book The Radio Phonics Laboratory: Telecommunications, Speech Synthesis, and the Birth of Electronic Music from Velocity Press and available on Bookshop.org, Amazon, and fine bookstores everywhere.

Justin Patrick Moore :: Your father was a mathematician at Bell Labs, and worked on the Music For Mathematics LP. What was his role in the group that worked on putting the record together?

Don Slepian :: He helped lead a small project in aleatoric composition that Max started. Each mathematician was shown 4 bars of written music and asked to contribute 2 bars to follow. This was repeated for each participant. My conclusion was that a composition really needs a single composer with a vision. The result of the experiment was a rather unfocused piece of music that wandered every few bars.

How long did your father work at Bell Labs and what other kind of projects did he work on there?

DS :: David Slepian worked as a mathematician at Bell Labs for 33 years. He extended and applied the work of Claude Shannon and made fundamental contributions to Information Theory and Coding. His work on coding contributed to the Joint Photographic Experts Group image compression scheme, the well-known and widely used .jpg image format that underlies the modern internet. (Wikipedia | Obit)

Listening to the test pressing of that LP that your father brought home inspired you to want to make electronic music of your own. How did you go about building your first synthesizer?

DS :: My father let me use his workbench and tools in the basement and he let me set up my own work spaces in other rooms. As I entered first grade he taught me how to make a good solder joint, how to trace a circuit, and how to use his analog multimeter to measure voltage, current, resistance and solve electronic mysteries. As a treat my parents would let me bring home old radio and television sets from the Summit dump. I would devour them in my basement room, taking all the parts off, experimenting with them and dreaming of the day that I could build something new of my own. As I sorted all the parts into different bins, I learned the names of every part in a radio or television and what they did. I especially prized the loudspeakers that I pulled out of radios.

Let me pause for a moment to describe the Summit Dump as it was in the early 1960’s. You drove under a railroad trestle and up a short driveway into a large garage where several gentlemen held court and did a quick triage on every load coming into the dump, putting aside for their own use anything that might strike their interest. Depending on what you were dumping you were directed to one of a dozen large mounds of Summit’s discards. The moment the car stopped I would immediately head to the electronics pile to assess the day’s revealed treasures. I once found to my excited delight a thick bound manual marked “Classified: Department of the Navy” marked 1942 describing the construction of a ship bound radar set with complete drawings of obsolete tube circuits. I found old radios and television sets galore. I found car horns in a variety of pitches, enough to combine with a strong 12 volt DC power supply to build a car horn organ to the annoyance of anyone within earshot. Piece by piece I would drag these treasures back to the trunk of the car, and my indulgent parents allowed me to bring home at least three or four new projects, my treats from visiting such a magical place.

“One day in an inspired moment I wired one of my tiny DC motors in series with a loudspeaker and created my first electronic oscillator. I already knew how to use a potentiometer to vary the DC voltage. Now I had something that sounded like an electronic mosquito that I could play with a knob!” ~Don Slepian

I had a collection of little low voltage DC motors that I loved. The motors would make a tiny acoustic sound that varied depending on how much voltage I sent to the motor. I was forever burning them out with too much voltage, and I learned how to heal the broken ones by taking them apart, cleaning the brushes and armatures, and blowing out bits of carbon from any unfortunate fires. One day in an inspired moment I wired one of my tiny DC motors in series with a loudspeaker and created my first electronic oscillator. I already knew how to use a potentiometer to vary the DC voltage. Now I had something that sounded like an electronic mosquito that I could play with a knob! Boy, was I thrilled! It was my first electronic music instrument and I made it myself.

Unlike car horns with fixed pitch, I could vary the pitch of these little motors with a knob. An example of one of my favorite little DC motors. Other kids used them for slot car racers. I just liked them for the sound that they made. When I was in second grade, my Dad taught me how to draw a simple schematic to diagram my first Electronic Oscillator circuit. The Potentiometer was a big fancy wooden knob that I found on an old radio set in the Summit dump. I would grab that wonderful knob and change the pitch of the motor. That became a big loud squealing sound coming out of the loudspeaker, a sound I could control and play with my hand. I built other instruments my first years in Summit.

You grew up in a scientific family, and got to meet Max Mathews at a very young age. How did being around cutting-edge technology and its creators effect your sense of creativity?

DS :: I was grounded in electronics and aspects of computer science from an early age. My application was always in music and the creation of new musical hardware instruments.

Being around so much communications technology and people interested in it, I am sure a lot of folks at Bell Labs had their amateur radio license. Was your father licensed as a ham, and was this an area of technology you have had any involvement with? (Your use of teletype prompted this question… and I am a ham myself, so was curious.

DS :: I have been around hams all my life and as a child I loved my short wave radio for the wonderful sounds I harvested from the ham bands. No, I never had the pleasure of broadcasting myself.

Back in 1968 when I was 15 I composed a musical piece for three teletypes (“The Chunka Ding Trio”). In my high school we had three teletypes as I/O for a DEC PDP8/i minicomputer. I learned the CTL-G code that rang the teletype bell and the CTL-L code that forced a linefeed. I made a rhythmic track of these two codes, sounding like “ding chunka-chunka ding ding chunka-chunka”). I cut the slightly oily yellow punched tape where I had recorded these codes, gave it a single twist, and carefully spliced the beginning to the end of the yellow punched tape, creating a loop. I was so pleased with this creation that I created two more variations to this loop and fed it to the other two teletypes. The three teletypes going together would drift against each other, producing a rich ever-changing cacophony of chimes and thunks. When the math teacher who was in charge of the computer room walked in on this impromptu concert he immediately started looking for me. I can’t imagine why.

Did you write your own programs for MUSIC, or were you mostly interested in hardware at the time?

DS :: I did write a number of scores in MUSIC V in C under UNIX during the late 70’s. My main interest was hardware, building filters and oscillators using early opamps like the u741. I later fell in love with building new devices using the TL074, a quad bifet audio opamp that enables so many electronic music circuits.

In 1971 Mathews hired you to become a technician for his GROOVE system. What was your experience working with GROOVE and did you make any of your own music with the system?

DS :: I was hired during the summer after I graduated high school as a wiring technician in the GROOVE output room. I was fascinated by GROOVE but my primary work that summer was building a hardware synthesizer as a gift for John Pierce who was retiring at that time. We were making fixed tuned resonance circuits derived from Max Mathew’s electronic violin in an early attempt to synthesizer musical timbres from noise sources.

Who else was making music with GROOVE while you were a technician there?

DS :: I was most influenced by the work of John-Claude Risset who was kind and generous enough to take an interest in my passion for computer music. I was fascinated by his Shepard-Risset glissando and the barber pole effect. I was excited to interact with the composers that worked with GROOVE at that time. Later, in 1984 I did a one week performance residency at the Pompidou Center where I saw the IRCAM institute that was led by Jean-Claude Risset.

From my chronology this was just a few years before Laurie Spiegel started working with the system. Did you cross paths with her at the time, or later when you came back from Hawaii?

DS :: I spent time with Laurie Spiegel later in the 80’s where our paths often crossed. I was an early user and booster of “Music Mouse,” her innovative music generation software. I have always admired her compositions and her pioneering spirit.

You went to Honolulu in 1972 where you taught classes for users of Arp Synthesizers and also stocked and sold them at Sinergia Studios where you worked. This was also the time period when you became a tester for ARPANET, the Department of Defense project that was the early version of the internet. How did you end up becoming a tester, and how did this relate, if at all to your journey in electronic music?

DS :: I became involved with the ALOHA project, the radio transmission of packetized data that helped create the TCP/IP protocol suite and the ARPANET through my father’s friends, Norman Abramson and Frank Kuo. I ran a testing outpost that was a teletype and a buffer/transmitter on the third floor of a university building that had a line of sight to the University of Hawaii’s computer center. I played text-based games on the early internet when there were only 16 non-classified places to go. I was a 19 year old kid who was mad for technology in any form.

You coaxed serene and beautiful sounds out of the Hal Alles synthesizer. In your article Memories of Max Mathews you mentioned how Mathews could be emotionally distant, and that he also had a tin ear. In a similar vein some avantgarde electronic music can sound clinical. How did you bring your human touch to technology to create warm and emotionally rewarding music?

DS :: I studied and played acoustic instruments such as guitar, piano, orchestral harp and recorders. I added analog processing to digital sounds to warm up cold timbres to sounds that would please my ears. I grew up listening to baroque, classical and romantic music as a result of my father’s taste in music. I used controlled elements of randomness in both musical composition and sound processing to make the music of my imagination.

Laurie Spiegel was working with the Alles synth while you were a resident artist. Who else was using the machine?

DS :: Both Laurie Spiegel and Larry Fast would come by to do some recording. I spent and afternoon with Bob Moog showing him the Alles Machine. From the fall of 1979 until 1982 when the machine fell into disrepair I was the only one working with it on a daily basis. Besides “Sea of Bliss” I made a 5 other pieces of music using the instruments unique properties.

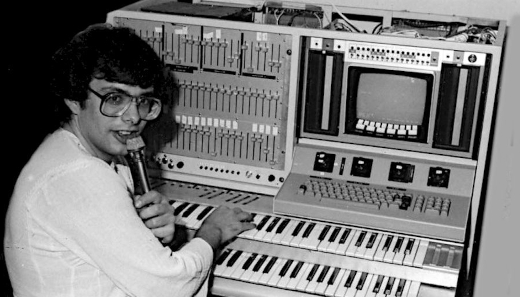

There are pictures of you at Bell Labs holding a mic with the Alles synth. Was the mic for demonstrating the machine, or were you processing vocals through it or something else?

DS :: The Alles Machine had a very early and somewhat crude implementation of digital reverb and digital pitch-shifting. I drove both using my voice through the microphone.

Have you worked with vocoders or speech synthesis in your work?

DS :: In the late 80’s I worked with the Telecommunications For The Handicapped project at BELLCORE, Bell Communications Research. I built a voice-controlled jukebox with several dozen spoken commands that would control a musical sequence. We trained it with the damaged speech of cerebral palsy children at the NJ Metheny School. It was wonderful to see the excitement of the children as they controlled music from their utterances.

There have been plenty of other synthesizers before and after the Alles Machine, but do you miss working with this one-of-a-kind instrument?

DS :: Doug Beyer was the software architect of the Alles Machine and a great innovator. I am working with Stuart Diamond and mathematician Chuck Heaton to create software that will bring some of his innovations that were part of the Alles Machine to the present world of MIDI.

Your music has been described as New Age. Is that a moniker you accept? There has always been some crossover between ambient music and New Age music. How do you feel each label applies or doesn’t apply to your work?

DS :: I am entirely focused on live performance of improvised electronic music in baroque, classical and romantic styles. Perhaps “classitronic” would be a name for this genre, but not really, since I am improvising new music and not reproducing compositions from the past. Neither “New Age” nor “Ambient” would accurately classify my current work. I seem to be well tolerated by the kind and gentle community of composers in the “Ambient Electronica” genre since I perform on electronic keyboards. Listen here for many examples of my live improvised electronic classical music.

Do you work with modern iterations of MUSIC either in Pure Data or MAX/MSP?

DS :: No, not currently. All of my MIDI programming is done using Plogue Bidule, a visual abstraction layer that lets me connect MIDI control surfaces to custom hardware while simultaneously being a very lightweight VST host. For the past 12 years it had been my main tool.

You mentioned on your website that you write and build instruments. What kind of instruments are you building and what are you writing these days?

DS :: Currently I am developing hardware to better interface both feet and tongue as computer controllers as I build a new instrument I’m calling the FootNote or Pedaphon. I’ve entered the world of Arduino controlled interfaces in my pursuit of better electronic musical controllers.

How did your experiences at Bell Labs affect your subsequent work?

DS :: The open and collaborative culture of Bell Laboratories during its golden years has helped me find fruitful collaborations with other musicians and researchers. It certainly has influenced my present work at EMEAPP (the Electronic Music Education and Preservation Project) and the nascent Music of Music Technology.

![Allmanna Town :: 1911 EP (Self Released) — [concise]](https://igloomag.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/allmannatown-1911_feat2-75x75.jpg)