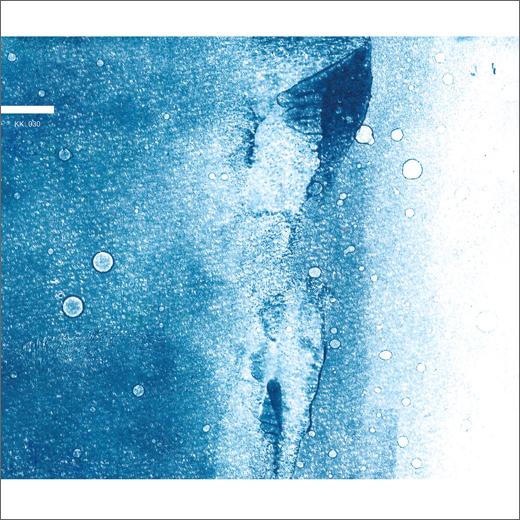

Like nature herself, Mizu no Katachi is neither minimalist nor maximalist, but equal-tempered, the earthbound reality of Pythagoras’ postulated “music of the spheres.”

Coming from a place where it’s cloudy and rainy all year, percussionist Kazuya Matsumoto says he hears an “accidental orchestra” whenever he takes a walk. For his debut solo album, he decided to conduct that orchestra.

Water was the first element, covering all but two or three percent of the earth’s surface, a place devoid of any life but bacteria and algae. Thus water made the first music, surging and sloshing in fluid rhythm, evaporating into the sky and pouring back down. With the emergence of the continental crest, it had something to bang, wash and sing against.

Matsumoto provides concise but detailed notes for each piece on Mizu no Katachi (“the shape of water”), housed in a handsome, recumbent rectangular package, a very slim book actually. About location – limestone cave, concealed river, ocean shore—and instrumentation and emotion. Focusing more on resonance than anything we would commonly identify as melody, he achieves consonance, an intelligent clangor that soaks the listener. Key to Mizu no Katachi is the fact that it is “un-rhythmical,” an adjective otherwise anathema any drummer. Every drop, no matter what surface it hits—soil, metal, liquid, or air—water turned mist—is unpredictable and sounds unlike the one before.

Some pieces happened immediately, he writes, others of the course of years. Only “non-instruments” have been used (although I would swear to hearing electronic undulations on “Higurashi Sonohigurashi”). Aside from the water itself—running ever seaward, striking land with small violence as rain, perhaps spanked with bare palms—he deploys singing bowls, gongs, and most memorably, a slit metal gourd called the hamon, created by sculptor Teppei Saito, which for Matsumoto evokes the suikinkutsu, a staple of Japanese landscape art. Field recordings—insects, frogs, birds—are sometimes left unadulterated, sometimes accompanied by a single, shimmering gong. Crickets hiss and cicadae that whirr, a bowed bowl sounds like a sad cuckoo. The bonfire he lights crackles in remarkable mirroring of the falling raindrops.

Like nature herself, Mizu no Katachi is neither minimalist nor maximalist, but equal-tempered, the earthbound reality of Pythagoras’ postulated “music of the spheres.”

Mizu no Katachi is available on Spekk.