Igloo Magazine presents a serialized, long-form oral history of the work of Jack Dangers, front man for Meat Beat Manifesto, Perennial Divide, Tino Corp, The JDs, and countless other monikers. These monthly installments will hopefully provide a definitive insight into the works of the man (originally) from Swindon, underrated genius of the last 40 years, and pioneer of three distinct musical genres of the late 20th and early 21st century. Chang Terhune’s interviews take twists and turns as he seeks to plumb the depths of this musical mind in a series we’re calling “Storming The Studio: 40 Years of The Future Worlds of Jack Dangers.”

The hi-fi set from the early 1960s and the Garrard RC88/4

The Garrard Engineering and Manufacturing Company, founded in Swindon, UK in 1901, produced high-quality gramophone turntables. These were among the first “transcription” turntables that supported all extant commercial playback formats—the 33, 45 and 78 rpm records. These are still highly sought after today for their quality engineering and construction.

My father bought a turntable as part of a hi-fi set in the early 1960s: the massive Garrard RC88/4. Even from a young age I was drawn to music and thus to this strange dark device I was forbidden to use unsupervised (I was perhaps five years of age, very curious and highly adverse to following orders). Though it intimidated me with its heavy tonearm, strange multi-platter spindle, and the warm glowing tubes of the amplifier like something out of James Whale’s “Frankenstein” I loved to hear it play music.

It was on this machine that I first heard The Beatles, Donovan, Glenn Miller, Pete Seeger and others. These artists were among my parent’s favorites and through listening to them I was introduced to one of my passions, and perhaps addiction which is, of course, music.

A stereo playing a record or tape was an escape and a window to other worlds.

Eventually I’d acquire my own stereo and my own music. In a world where I often felt out of place and misunderstood music was a solace, not uncommon for those of us who felt different and out of place in their surroundings. My town was a place where sports and the grades to make it into an Ivy League college were the rule of law. As an un-athletic, ADD(led) kid growing up in those wealthy suburbs outside of New York City, a stereo playing a record or tape was an escape and a window to other worlds.

But the old Garrard RC88/4 wasn’t the only gateway. There was of course radio which around 1980 was bursting with new and exciting music. Before I had my own stereo I had a simple Japanese AM/FM clock radio on my bed stand. As a kid I’d spend hours scanning the dial for kindred spirits out on the airwaves (my fascination with radio began with listening to a mammoth Zenith shortwave radio at my grandparent’s cabin in Maine).

Scanning the dial for kindred spirits

From the cautious, furtive spinning of the FM dial in the night when I should’ve been studying—or if it was later, sleeping—I discovered the second British invasion with first punk then new wave washing across mine and many other young ears. In this music I found something more exciting and alive than anything else on the radio (with the exception of the seductive and funky music on the high end of the dial which would soon be called hip-hop). The stripped down and raw sounds coming from the UK, Europe and parts of America shaped my tastes as I began to seek out the artists making this music to satiate my new hunger.

Around this time, I remember being dragged by my parents to a dinner party in New York’s Chelsea neighborhood. There was another kid roughly my age there, though it mattered little as my shyness was nearly impenetrable. But as the adults were even more boring, eventually I found myself sitting on a staircase in this apartment with a strange kid and his cassette player. One of the tapes he had was Computer World by Kraftwerk which an older sister had recorded for him as well as drawing the album art in felt-tip pen on the J-card. Within seconds of hearing that intense pulsing title track I was hooked on something previously unknown to my ears. I pushed past my shyness and made him play it over and over again until we left late in the evening.

I searched out new music, consuming it with a hunger usually reserved for butterscotch pudding or mom’s spaghetti.

Within a few years I went from listening to classic rock to new wave to electronic music such as Kraftwerk which soon led me to the music of Joy Division, then New Order, Ultravox to Depeche Mode, then Cabaret Voltaire. Through this mixture of radio, then records, then tapes, plus word of mouth, I searched out new music, consuming it with a hunger usually reserved for butterscotch pudding or mom’s spaghetti.

Eight years later I landed a job working at my favorite record store in my hometown, Johnny’s. Here the town’s youth got their fill of music from the popular to the weird (the end of the spectrum I gravitated towards) while a select few found refuge in the weird and wonderful clothes and posters John Konrad sold there. In this way Johnny’s Records was a gateway unto itself, a glimpse into a world beyond our quiet, preppy town (it bears mentioning that a previous employee of Johnny’s was Moby who attended high school with my brother. This bears noting as it was from working at Johnny’s that Moby’s said his own love of music was enhanced and nurtured).

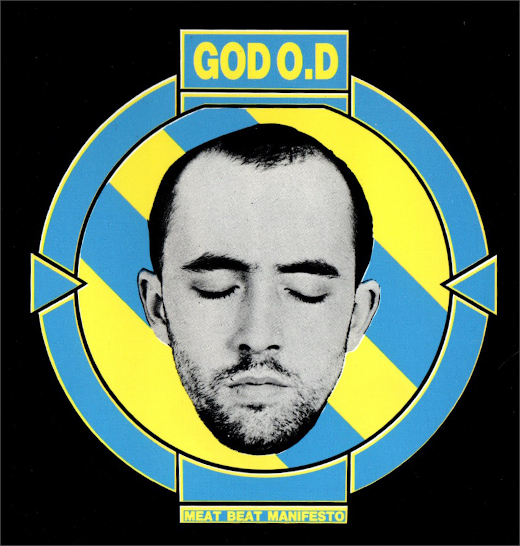

“God O.D.” is run through my head

One day a strange looking album arrived with the day’s delivery; its cover design was black, blue and yellow with strange faces on it. It looked like nothing so much as a warning sign or cypher of some kind. My co-worker and best friend Jay looked at me then shrugged before dropping the needle on its outer edge.

Instantly, our minds were blown and lives irrevocably, wonderfully changed within milliseconds of hearing the thundering opening drum break of “God O.D.” by Meat Beat Manifesto. From then on I’d hunt down everything I could find by the band and the madman fronting it who, of course, was Jack Dangers.

The story of my musical awakening isn’t all that unique, as profound as it felt to me. Stories of someone’s life changing upon hearing a single song are numerous and far from unique. Yet my reason for telling it here is it emphasizes the power of music; to show us a glimpse of a life beyond our world, our family and our circumstances.

The power of music; to show us a glimpse of a life beyond our world, our family and our circumstances.

Especially to those misfits, artistic kids born into working class or non-artistic families. Which was the case for a boy in growing up in England a few before me, though the path was slightly different.

“I’d be listening to radio Luxembourg underneath my bed clothes at night with a torch,” Jack Dangers replies. “When when I was 10 I heard “I’m Not In Love,” by 10cc and it was the best thing I’d ever heard,” says Dangers. “To this day, I think it’s the best pop song written for sure. It beats anything by The Beatles or The Beach Boys. And it’s completely electronic as well! It’s phenomenal, that song is.”

“But (growing up) I didn’t have a record player or anything like that,” says Dangers, “so I couldn’t even listen to any of this new music. When I started buying records I’d have to go around to my friend’s house ‘cause he had a record player then I’d record it onto cassette. And then I’d borrow his tape player ’cause I didn’t have one of those either! I mean we didn’t have bloody anything growing up. We didn’t have a car, didn’t have a telephone, didn’t have a color TV or one that was working. Like we had fuck all while (other families in the wealthier parts of town) were living it up in Penn Hill going on holidays and shit and I didn’t do anything, didn’t go anywhere!” he says, laughing.

Stuck in 1979: “Trans-Europe Express” grabbed Jack’s attention forever

“But even then I wasn’t old enough to appreciate John Peel or stuff like that. That all changed in ’79 when I was going out with this girl from that same street three houses down and one street over from where Andy (Partridge) of XTC lived. That’s when I heard Kraftwerk’s “Trans-Europe Express.””

Yes, those Germans and their entrancing, addictive music. But it wasn’t Computer World, the album which so enthralled me, that grabbed Jack’s attention forever.

(“I’m Not In Love,” “Trans-Europe Express” and “Dancevision”): When brought together and mixed in the right way inside the right fertile mind created that prime audio soup rich with many ingredients.

“Phil Lynott from Thin Lizzy was on a program where they got pop stars to play on their top 10 favorite songs and his number one was “Trans-Europe Express,”” says Jack. “And when that came on it was like, wow, this is unlike anything I’ve ever heard! And that was three years after it came out. And it seemed like a couple months later I heard the Holiday ’80 EP by The Human League then “Dancevision Instrumental.” And then that was it! I was off and running from those three tracks right there: “I’m Not In Love,” “Trans-Europe Express” and “Dancevision.””

Hearing this sets off a nuclear bomb in my mind.

You can hear elements of these tracks in MBM’s music; melodic, ethereal drones and pads, the tight, metallic rhythms and the warts and all approach Jack takes in wrangling his army of vintage analog synthesizers,

Ever since hearing “God O.D.” in 1988 and Meat Beat’s subsequent releases I sensed an underlying framework, a sonic foundation upon which Jack’s musical house was built. Unlike classic rock icons such as The Beatles, Led Zeppelin or The Rolling Stones whose blues and R&B influences are abundantly clear, there’s a certain element threaded through Meat Beat Manifesto’s music which I found elusive and indefinable until that moment Jack named those three tracks. Each unique in their own way but when brought together and mixed in the right way inside the right fertile mind created that prime audio soup rich with many ingredients.

You can hear elements of these tracks in MBM’s music; melodic, ethereal drones and pads, the tight, metallic rhythms and the warts and all approach Jack takes in wrangling his army of vintage analog synthesizers.

Clock DVA, Heaven 17, and The Human League

“Oh, you know what the weird thing is?” says Jack. “I’ve been doing a project with Adi Newton from Clock DVA/The Anti Group.” My jaw drops to the floor though I manage an inquisitive “Oh?” after I pick it up.

“Yeah, he was in the studio and I have the actual synths they used, The Human League synths. He worked with them on that track, on “Dancevision” in 1977. And there he was in my studio looking at the same synths he hadn’t seen in 40 years.

“Yeah, it’s frankly so important to me,” Jack says. “When I first heard “Dancevision” I thought I was lucky enough just to get it. Then about 10 years later in 1989 I was looking for synthesizers in London. And they had this Roland modular sitting in a shop there. I was looking at it, saying, “Well, how much is that? Where did you get it from?” Then he said, “It’s on consignment from Ian Craig Marsh.” Yeah, the Ian Craig Marsh from Heaven 17 and The Human League! So I immediately knew what it was and bought it straight away. Then to work with Adi on a track with those synths—well that was the cherry on the icing on the cake of Sheffield and my homage to it.”

“To work with Adi on a track with those synths—well that was the cherry on the icing on the cake of Sheffield and my homage to it.”

At this point in our conversation about musical awakenings I mention my own family’s hi-fi and the records I played. Out of curiosity, I end up Googling it only to make a startling discovery. Did you know the Garrard RC88/4 was made in Swindon? I ask him.

“Yeah,” says Jack. “They made those and pressed records in a plant there as well for EMI and Parlophone.”

My parents copies of Rubber Soul, Sgt. Pepper’s and Meet The Beatles were all imported first pressings, I say. Played on the Garrard RC88/4 purchased in the early 1960s.

“Really?” he says. “My mum worked in that factory. There’s a very good chance she not only built the turntable your folks had but she probably assembled the sleeves of one or all of those Beatles records.

This time I’m unable to mask the sound of my shock and surprise, the implosion of my sharp inhale at these revelations. Though separated by a few years and a few thousand miles it would seem the Dangers family had impacted me perhaps twenty years earlier, not in 1988 when the sounds of “God O.D.” burst forth from the suspended speakers in a cramped record store in suburban Connecticut, but from the single tower speaker in the living room of my childhood home.

Next time—Part 5: “It’s The Music.”

Graphic by Digital Chemist

![Hasbeen :: Bunker Symphonies II (Clean Error) — [concise]](https://igloomag.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/hasbeen-bunker-symphonies-ii_feat-75x75.jpg)

![Extrawelt :: AE-13 (Adepta Editions) — [concise]](https://igloomag.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/extrawelt-ae-13_v_feat-75x75.jpg)

![Beyond the Black Hole :: Protonic Flux EP (Nebleena) — [concise]](https://igloomag.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/beyond-the-black-hole-protonic-flux_feat-75x75.jpg)

![H. Ruine, Mikhail Kireev :: Imagined / Awakenings (Mestnost) — [concise]](https://igloomag.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/h-ruine-mikhail-kireev-imagined-awakenings_feat2-75x75.jpg)

![Squaric :: 808 [Remixes] (Diffuse Reality) — [concise]](https://igloomag.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/squaric-808-remixes_feat-75x75.jpg)