(09.05.05) Break-dancers burst out of the crowd; hyperkinetic acrobats that twist and turn, bounce off linoleum flooring like spring-loaded contortionists. MC’s enter stage left, get the crowd going, then are quickly engulfed by it; a spotlight searches, shines on no-one and everyone. Lasers cut through the smoke of dry ice, a movie flickers on one wall, and the whole place vibrates with the thump of beat and melody. At the front of the room, a hi-fidelity priest in multi-colored vestments hulks over the ones and twos like a fullback with the nimble fingers of a career stenographer, keeping the flow in check, fondling grooves like rare and precious jewels.

It’s a spontaneous, raucous scene – makes you want to go buck-wild. Not just another concert, this is a performance. And if James Brown is the hardest working man in show business, Afrika Bambaataa and his crew have to be 2nd. From the moment the needle drops, it’s on and it keeps going.

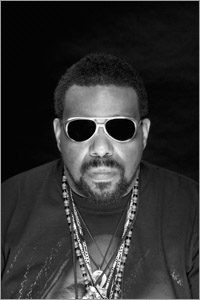

He was recently in Seoul to perform at a swank new downtown club and I met him at his hotel the morning before the show. The lobby was full of western tourists and Korean businessmen. Bam looked like a jet-lagged giant who had dropped in from outer space. A big man, he slowly lumbered across the plush carpet of the reception lounge; an array of necklaces draped around his thick neck. After slumping into an overstuffed chair, he reached out to shake my hand.

King Kumonzi, the official spokesperson for The Zulu Nation, and another of Bam’s entourage, King Tone, soon joined us. This is part of his extended family, The Zulu Nation.

Samuel Stackhouse :: What is The Zulu Nation all about?

Afrika Bambaataa :: It’s an international hip-hop awareness movement. Last millennium we were all into keeping people aware of hip-hop, the music part, and what’s going on. And this millennium we’re trying to get more into the economic part. We want to start a universal federation for the preservation of hip-hop culture, and a museum in The Bronx where it all started.

::..:::…..:..::….:::::..:::..:::::::……:::…::.:::….::::..:..:::…::…….:::::

The Zulu Nation evolved out of Bam’s days with the notorious Bronx River Project’s street gang, The Black Spades. But by 1973 The Black Spades were fading. Bam had already earned a reputation for his turntable skills and his soon to be defunct status as The Black Spades warlord gave him a reputation and a base for his party crews. Soon a large collective of DJs, rappers, break dancers, graffiti writers, what Bam refers to as the “four elements of hip-hop culture” would begin following him from show to show. Not long after, Afrika Bambaata officially called this The Zulu Nation.

::..:::…..:..::….:::::..:::..:::::::……:::…::.:::….::::..:..:::…::…….:::::

Samuel Stackhouse :: So when was the true birth of hip-hop?

Afrika Bambaataa :: Hip-hop as a name started in 1974. We named it then. Before that, Lovebug Starsky used to say “to the hop” and Keith Cowboy added the hip and they was saying “hip-hop.” I said “yeah, well that’s funky enough. You know what, let’s call this culture ‘hip-hop.’

But you got to get your facts straight: who was there and who started it, and what was it before that. Rap’s always been there, from Cab Calloway, up through the Last Poets. It’s just that when we came along we decided to call all of what we were doing hip-hop.

Lots of people were doing similar things back then but nobody had the unity like we had when I formed The Zulu Nation. So I said, well we’ll call this our own culture and we’ll be proud about it and hope other brothers come under The Zulu Nation.

There were the four elements, (the dj’s, the rappers, the dancers, and artists) and we added that fifth element: the knowledge. Knowledge is what holds it all together. But that fifth element is really the first element. We’re trying to wake people up to true hip-hop culture by bringing them to that fifth element, not what the media and the money people would make you believe is hip-hop culture.

Samuel Stackhouse :: Does The Zulu Nation have any religious affiliations?

Afrika Bambaataa :: All religions. We don’t get into our personal beliefs, don’t fight other humans about Allah, Jehovah, or Yahweh, because we believe they’re all talking about the same being. People get caught up in the Bible or the Koran or forget about all the other ancient books out there with knowledge from all over the planet from all times. And that’s what Zulu is about. That’s what we try to come out with factology: right knowledge, right wisdom, right understanding so we can ‘overstand’ and find right reasoning. We want black, brown, yellow, red and white people feeling the same vibrations of the planet.

Samuel Stackhouse :: And what is it that’s most important to “overstand?”

Afrika Bambaataa :: Above all, we need to know that we got to start protecting Earth because she’s a living entity. If we keep doing things to the planet in destructive ways, she’s not going to be playing. It’s not nice to fool with Mother Nature.

It’s the job of every human being on the planet to help the next person live comfortably… but there’s a greedy click of people who want to be what we call “Luciferians” and control things for money and steal the resources of Earth.

Samuel Stackhouse :: What are your thoughts on today’s music industry?

Afrika Bambaataa :: A lot of people, when they get caught up in that money part of hip-hop, lose their soul and forget what the whole thing was all about. If you notice, you never see any of the true school or pioneers or architects, like Grandmaster Flash, invited to certain summits or events because the money making-machine wants to keep it to what they want people to think it is.

It’s a whole brainwashing thing with the MTV’s and BET’s. To me it’s buggin’ people’s minds out. These video shows started out good, but as the money and everything jumped in (and I’m not saying there’s anything wrong with making money) but now they’re using these shows to make people blind, deaf, and dumb – slaves or zombies to the rhythm.

It’s almost like a split-apart-tide now in hip-hop. You have the people who follow hip-hop culture and you got the people who just follow rapping.

Samuel Stackhouse :: What do you think of some of the current MCs, or” rappers?”

Afrika Bambaataa :: A lot of them just strictly want to do their record. They can’t really throw down on the mic for 15 or 20 minutes, or get into a real battle. Or even stay away from using profanity.

Samuel Stackhouse :: What about the other elements, the dancing and tagging, will they come back to prominence?

Afrika Bambaataa :: There’s a big scene still out there for the dancing. It’s just not being covered. There’s even a Korean crew that’s going to be at the show tonight. Until the media decides to re-discover it, I guess you’ll only see what they want you to see. You know everything goes in cycles.

There’s The Rock Steady Anniversary, The Hip-Hop Elements, The B-Boy Summit, The Battle of the Year in Japan. There’s a lot people trying to keep this alive but the media just isn’t covering it. It never really went nowhere. It’s still out there.

Samuel Stackhouse :: Who are some of the current artists you like?

Afrika Bambaataa :: I’m crazy about a lot of the French hip-hop. I like Ms. Dynamite from England. And I’m all about Missy. Missy I believe is the greatest young artist of hip-hop culture. She’s rockin’ the house and trying to keep the flavor of b-boy and b-girl culture. There’s also still a lot of the true school out there rocking the house.

Samuel Stackhouse :: What do you think about the hip-hop that gets played on the radio?

Afrika Bambaataa :: Companies like Clear Channel are trying to control all the radio stations, all the so-called black stations. A lot of these stations’ program directors are trying to program the mind.

I respect the satellite stations because they’re more open to play all music. Even when I listen to their hip-hop stations, I’ll hear Kraftwerk and James Brown. And there’s a lot things happening with internet stations, but the money people are trying to get control of that too.

Samuel Stackhouse :: You’ve always been known for using many different kinds of music, like electronic music such as Kraftwerk.

Afrika Bambaataa :: I’ve been DJ’ing all over the planet and lots of folks been coming out experiencing true hip-hop culture for the first time. They’ll hear a rap record, then maybe break-beat, some James Brown, then maybe some Hip-House, Trip-House, electronica and all that. So when people say they’re into hip-hop culture, then you gotta bring in all of it. Not just some of it – you can’t just take little parts. People say ‘ah I ain’t into that House Thing. I don’t like this techno.’ People forgot that all other music made up hip-hop.

::..:::…..:..::….:::::..:::..:::::::……:::…::.:::….::::..:..:::…::…….:::::

And he doesn’t forget any of that music. He might rhapsodize or drop “factology” off-stage, but as the minister of beats, he spins vinyl like prayer wheels, caught up in the moment, oblivious of himself, aware only of the crowd and the records that speak for him. At his shows you can ride the double-dutch bus, do Le Freak With Chic, and shake and finger-pop. You also can do some easy-skankin’, right before vintage AC/DC starts shaking the speakers. After all, this is the guy who cut a record with punk rocker John Lydon (a.k.a. “Johnny Rotten”), worked with experimental electro-guru Bill Laswell, as well as threw down the funk with the Godfather himself, James Brown. At an Afrika Bambaata show, you can expect to hear almost anything, including spoken word, like the speeches of Malcolm X and Martin Luther King he has been known to put into the mix. The man truly loves music and respects the multitude of ways it can be played and enjoyed.

This is why Afrika Bambaataa is relevant: not just because he’s a founder of hip-hop music and culture. Afrika Bambaataa is crucial to the continuing development and success of both because he’s a true devotee to his craft and because he’s one of the few performers out there who knows that a great show is about the showmanship; he knows it’s about rocking that house party, or that club. From the rec rooms of South Bronx projects to a funky new club in the heart of downtown Seoul, Bam keeps it real by making sure the music lives not for the entertainer but for the audience.

Later that night, just as midnight was saying hello to morning, I headed back to the crib. There were still plenty of people getting their groove on. Bam was still up there digging through the crates, still spinning and spinning. High above, the ubiquitous disco ball caught fragmented reflections of this righteous, riotous scene: a writhing crowd of yellow, white, black, and brown wiggling and shaking their money makers; a bunch of beat junkies with a

sense that the whole planet truly was a rock we were spinning on and Bam was at the axis. I didn’t want to go, didn’t want to leave all that behind, but I was tired – tired and satisfied. I’d experienced something I truly hadn’t expected to find, something I thought was of the past or simply never was. Because this night had been how I heard it once was, back in the day, back when I was still wearing Garanimals and watching my sister dance to the radio. This was how it must have been when hip-hop was still just a name and not a commodity; or even before the name, when it was simply a way for folks to get together and have a good time.

Click here for more information about The Universal Zulu Nation.

![Hasbeen :: Bunker Symphonies II (Clean Error) — [concise]](https://igloomag.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/hasbeen-bunker-symphonies-ii_feat-75x75.jpg)

![Extrawelt :: AE-13 (Adepta Editions) — [concise]](https://igloomag.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/extrawelt-ae-13_v_feat-75x75.jpg)

![Beyond the Black Hole :: Protonic Flux EP (Nebleena) — [concise]](https://igloomag.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/beyond-the-black-hole-protonic-flux_feat-75x75.jpg)

![H. Ruine, Mikhail Kireev :: Imagined / Awakenings (Mestnost) — [concise]](https://igloomag.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/h-ruine-mikhail-kireev-imagined-awakenings_feat2-75x75.jpg)

![Squaric :: 808 [Remixes] (Diffuse Reality) — [concise]](https://igloomag.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/squaric-808-remixes_feat-75x75.jpg)