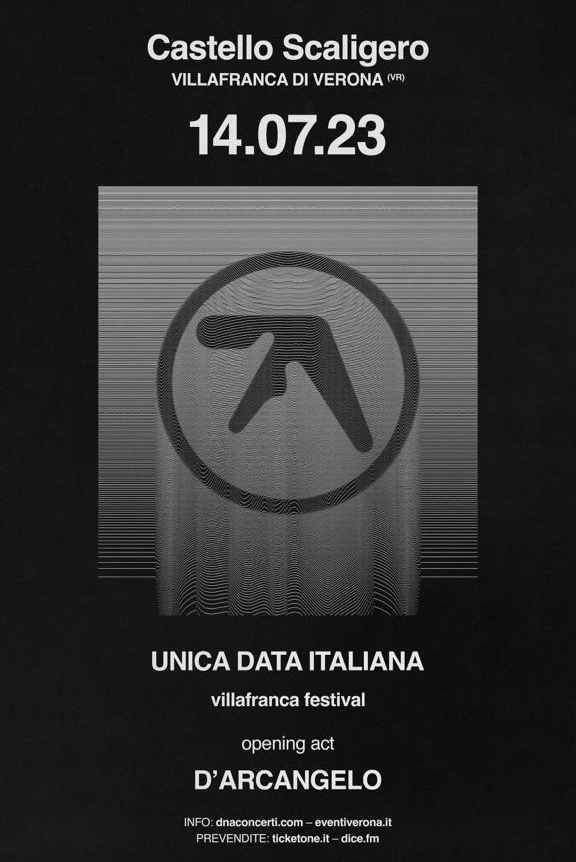

D’Arcangelo’s big break (worldwide) undoubtedly came in 1996 with their signing on UK’s Rephlex label, and this summer, Aphex Twin chose them to open for his show in Verona, Italy. In other words, this is the perfect occasion for a thorough retrospective interview with the experimental twins.

The electronic scene needs a voice

With a career spanning over 30 years, the D’Arcangelo brothers are definitely indissociable from the Italian electronic music scene. Their big break (worldwide) undoubtedly came in 1996 with their signing on UK’s Rephlex label, and this summer, Aphex Twin chose them to open for his show in Verona, Italy. In other words, this is the perfect occasion for a thorough retrospective interview with the experimental twins.

Christopher Mathieu :: You’re twins. Who’s the older one?

Marco :: We never thought who’s who, really. We never thought “Oh, we’re twins!” Well, we know we are but…

Where were you born and raised, and do you remember what introduced you to electronic music?

Marco :: We were born in Rome. Basically, it all goes back to probably the age of 10,11,12, because our mother bought our first record player, and I don’t know why, but we’ve always been interested in a certain sound, probably because we used to listen to radio stations like anybody else, and there was one radio station that would constantly play some different music from the usual music you could listen to in Italy. We were very young but there was one song at the time that really struck us. It was Thomas Dolby with this track called “Flying North” where he’s opening with this synthetic percussion, and I was just fascinated. Bear in mind that me and Fabrizio used to have a Commodore 64 console, and there was only one drum machine at the time. So, it was like: “Oh, we can do that!” But it wasn’t making music, it was just playing. Also, apart from what we used to listen to on the radio, there was Jean-Michel Jarre. At the time, he was big with “Oxygène”—he was in the charts—or even Cerrone with “Supernature.” So, that element of sequencers, we already knew that it wasn’t normal drums, we knew Cerrone was actually a drummer but we could hear the electronic instruments inside. That’s why we started, really, we were like: “Oh, we like that!”

Around what age did you start to compose?

Marco :: Probably around 21-22, more or less.

Fabrizio :: Listen to my brother because he’s lived in London. He’s had more memories. I just remember when I started to play for the first time with the Amiga. I know many people who did, and it was their first time playing on a PC. And I remember the first time we got to play with a tracker, it was the first time we played music in this kind of way. Marco and I got to play on it every night, and it was the first time we had musical content on a PC.

Are there references that are specific to Italian culture that you think have had a direct impact on your music?

Marco :: At the time? Yeah, there was a couple of them, like new wave. There was some listening to a group called Decibel with Enrico Ruggeri, who is very famous now, but even Matia Bazar, who used to have a single called “Elettrochoc.” If you listen to it, you can hear that this is absolute synth pop because they were a band that were influenced by the UK new wave. That was slightly before Italo-disco. There were many influences but one that influenced Italo-disco a lot was the Human League track, “Do You Want Me?” And from then, everyone was big on that specific way of writing sequences that sound similar and that became a common listen. If you listen to it, it’s just the same kind of composing because obviously, you know, why not do it? That’s how the music industry works, really.

How about Italian cinema?

Marco :: Everyone obviously references [Ennio] Morricone…

Fabrizio :: Also Goblin!

Marco :: Oh yeah, Goblin! It’s very difficult. In the 70’s, we have a huge list of composers in Italy.

Fabio Frizzi…

Marco :: Exactly. I was talking with Andrew Montgomery who is the lead singer of Geneva. We were talking about Goldfrapp. And I thought that on Goldfrapp’s first hit, “Utopia,” you can hear kind of like a riff which is obviously taken from Morricone. I can’t remember the title (“Tema Italiano” from The Sicilian Clan film- ed.) It’s like ripping off some part of his music and reinjecting it into it, but it’s okay because, you know, he’s one of the best composers we have, so why not?

1992 is the first year you started to release music with Automatic Sound Unlimited, which was a collaboration with Max Durante. What do you remember from this time-period?

Fabrizio :: Good question, man! (laughs) It was a strange meeting the first time. I remember to have the contact from friends of Max to help us create one of the biggest parties in Rome for the artists of +8 (Richie Hawtin’s first record label – ed.) and helped us pay so much in creating this fucking rave. I remember to have no good things to remember. More about money that disappeared. But, for the first time, me, my brother, and Max met together to late become Automatic Sound Unlimited.

Marco :: Well, basically, yeah, like Fabrizio said, we met because we used to be part of the organization of this rave party, which was the only one +8has ever done in Italy. Apart from the fact that whatever happened at that bloody rave, originally, we had this friendship with Max Durante. He knew someone at ACV (Leo Anibaldi’s record label – ed.), and at the time, I got a steady job—the first steady job I had—so it allowed me to actually buy a very expensive sampler. It was the Ensoniq EPS 16+, and we used to just gather at Max Durante’s house, you know, just having fun and playing music. So, we decided to have a go and ACV was very famous because they used to do decent production and then decided to have Robert Armani on board. He used to be in the studio when we presented them a demo tape, which was the first release we had, Roman’s Attak, which was a weird EP because we decided to make it our own techno. We liked it, no questions about it. Personally, I wasn’t there when they recorded it because everything was made at home, but ACV wanted to, you know, have some kind of control over the recordings. We obviously were naïve and young and were like: “Oh my God, we might ‘gonna have a chance for the record!” So we just let them do it. And that’s where it all started. They moved to a bigger studio and decided to have us on board.

In 1994, you created three projects: Centuria City, Automia Division and Monomorph.

Marco :: That was when we split from Durante because we had this rave party which, actually, curiously enough, you reminded me that we haven’t been 30, but31 years in music! And, on the 28th of August 1993, we had our first international gig, Energy 1993, where we met Aphex Twin for the first time. So, if I look back, I had completely forgotten how long we’d been making music for because we just love making music for ourselves; but anyway, we made Centuria City because after the A.S.U. double pack (Tu4Bx/0 = E.P.01 + Tu4Bx/2 =E.P.02 double 12-inch – ed.), we decided to split, because we just wanted to do something different. So, we had these two events.

Fabrizio, 5 years ago, you contributed to another record with Max Durante, The Experiment LP.

Fabrizio :: Exactly. I remember meeting together in Berlin at Max’s house. He said to me “Fabrizio, we have a new contract with a new label, why don’t we do new things together?” Why not? Because he’s a good friend of mine. And I remember playing 2 or 3 days together. I didn’t play many times in Berlin but sometimes we’d play DJ sets together with Max. Basic things but good things. We’re satisfied. Max is really a very good friend, and really a professional artist.

Around 1996, you made some great banging techno tracks, especially as Intermolecular Forces with Marco Lenzi. And you seem to have completely given up on the techno genre pretty much since the 2000’s. Is it just not inspiring to you anymore?

Marco :: Recently, Marco Lenzi had an interview where he explained the fact that we actually left to him the handling of everything that was Molecular. Molecular was started by me and him as he was working at the Silverfish record shop (in London,) and I had started working doing some promotion, etc. That’s exactly where we met Grant Wilson-Claridge for the first time. To cut it short, basically, I went to live in London because I had married a British girl, blah blah blah, and one day, I was walking by Charing Cross Road and saw this little cardboard thing saying that there was a record shop upstairs with techno, and I was very new. And while browsing, I found my records inside. And the guy who served me, Marco Lenzi, at the end, said: “Grant (Wilson-Claridge,) the guy behind Rephlex, he comes here to buy records sometimes. And we had one track in their fanzine, you know, before the internet-era. It had these little playlists where everyone used to have their little ten best tracks of the week or something. And this time, selected by Grant, there was one track from Automia Division.

“Diagram 2”!

Marco :: Exactly. He loved it. And I thought: “Oh! Amazing! He likes our track!” Nobody knows because we’re not used to hyping ourselves, but back at Energy ’93, before we left the hotel, they gathered all the artists, and I had a little chat with Richard David James (Aphex Twin.) It was just blah blah blah and I handed him the double EP of our tracks. He looked at it and he said “When was this released? I think I have it already.” And I was like “What do you mean you have it already?” And I was like “What?! Oh my God, he’s got my record!”

You were already quite experimental even before Marco Lenzi.

Marco :: Yeah, exactly. Centuria City was the hardest project. Automia Division was more on the melodic electronic side. I don’t remember why we decided to have this kind of split personalities, you know, but at the time, we thought it was okay!

Was it Grant who convinced you to just go by your own name? I wouldn’t be surprised.

Marco :: Yes, exactly. He said to us: “Don’t bother. Whatever you do, just release under your own name!” But with Intermolecular Forces, it was just playing. I mean, I remember clearly when we recorded the first demo. It was at Jason Mendonça’s house who is the actual bassist and vocal leader of one of the most interesting and important English death metal bands called Akercocke because he was behind this with his fellow Bob Bailey who was the owner of Zero Tolerance Records on which we released as Centuria. We thought we couldn’t use Centuria City due to rights, so we changed it to Centuria. They were very close and used to run a very hard techno / gabber club in London—the VFM (Value For Money.) At the time, everyone was very underground, very low profile. And this is why we learned to be low profile, because, at the time, there was so much to listen to, and everyone was friendly. Nobody tried to, you know, it was all very, very nice.

So, the straighter four-on-the-floor dancefloor stuff. You’re not interested in doing that anymore?

Marco :: When you grow up in the music industry, you make choices.

You can use another name.

Marco :: Yeah, we actually did! We have this kind of house record. I can say that to you, I don’t care. It’s called “Angels’ House.”

I don’t think I know this one. I know D Duo, Last Sinclair, Format HD.

Marco :: Format HD was a collaboration. That’s what I’m trying to explain. The synergy and the collaboration at the time was massive. Working in London, I was more in contact than Fabrizio. He used to work at home providing me with some back tracks and I had to finish the tracks, but differently from the rich people, we had to work to survive in London, so there was not much time to dedicate yourself completely to music-making, but it was okay. About “Angel’s House:” one day, I was invited to Germany, in Heidelberg, and this guy who used to run Under Cover Music Group, where I used to work, which is behind the famous Eukatech record shop, said to me: “Oh, can I lock you up in a studio? Just make me a track!” And I was like “What?” And I thought “OK,” Then came out these three very elementary 4/4 beat tracks that sound a bit housey, in a way. But it was nice. Obviously, we were so much more involved in making a demo for Rephlex, which was our main interest to have them release one, that we had to put everything aside and concentrate on that.

From your first EP on Rephlex, there’s this track called “Diagram VII (80’s Mix)” that has kept popping up on many DJ playlists ever since. It looks like it’s your biggest classic to date. Have you realized that?

Marco :: Yeah, yeah! It has become a classic for us too! And we’re ‘gonna play a new version of it. We often realize that for any artist. I mean, you’re our age, this is our generation. If you think of Aphex Twin, you’re going back to the first banging tracks or something like that, you know, and it’s curious, it’s like Duran Duran. if you think “Duran Duran,” you go “Rio!” It’s like nobody goes past that! Everyone’s like “Ah, yeah, yeah, I remember “Rio!” It’s a bit like this. Everyone remembers you for the early stuff, but I mean, there are lots that I obviously remember.

What were the Rephlex headquarters like back then?

Fabrizio :: What I remember the first time at Rephlex is a house in London. Two rooms upstairs with lots of records in one big room, like a big discotheque, and I remember Richard (D. James) playing. I remember being in the room with Grant, together, a garbage can and lots of unnamed demo tapes in the garbage. (laughs) And I remember listening to the way of choosing a demo tape from Grant. And lots and lots of great records everywhere, on the table, on the floor… (laughs)

Marco :: That was the headquarters, that changed, like, three times, for the record. And that’s Fabrizio’s logistic memory, but mainly, until the end, we received a lot of support.

Indeed. You’ve stayed with Rephlex from 1996 until 2013, which is pretty much, when they ended. That makes it the label you’ve stayed the longest with. What are your greatest memories from that time spent with them?

Marco :: The best memory we have of Rephlex in terms of record label and people was the good times we had and the love we received! A sense of being part of a family. They were highly professional, and we loved the laughter’s and the curry at the Indian’s! I mean, there was a time, just before the second album when we had a refusal of the first demo. And I just thought “Okay, that’s it.” I mean, we were lucky enough. But I had another bunch of tracks, which was made separately, and that convinced Grant to put out a second album.

Since then, we learned how to wait for a record because I must say that, like anyone in that type of relationship, we understand that we must wait. Because everyone now today is pushing to have a place in the music industry through social media, which helps a lot, no doubt. We found out so many good parties, so much good music out there, which hasn’t got a place because thing shave changed. And you know this, everything has changed. So, we are in this proper relationship in a way that he could tell us “Wait!” I mean, like any artists, we think this might work. And on the other side, he says: “No, this is not ‘gonna work.” So basically, Rephlex, the way they used to choose the records I was told by the man himself is to imagine yourself going to a record shop, browsing through the records and picking something up and go like: “I haven’t got this. I think this should be good.” So, it’s like, you know, something that you don’t have in your collection. And this is the way they used to choose tracks. He also he said to me “You’re the artist, but we are the producers, and we know what’s best for our record label. Don’t worry about it.” Because, you know, sometimes, they might choose a track you’re not very convinced of. Like “Diagram.” (laughs) That’s a fine example. I said, “I’m not sure this is ‘gonna work.” And there you go. They were right. (laughs)

You have been on various labels since. Is it difficult to find one you can stick with? Have you ever thought of just launching your own?

Marco :: Yes. Yes, for a long time. It’s difficult because, again, everything has changed, especially since Rephlex shut down. Obviously, we received quite a few occasional partnerships or requests for LP’s. We haven’t made a proper album since the last one we had, Audiovisual Designs (2013), which was kind of like a gift from Rephlex when he said “OK, we’re ‘gonna closedown…” We’re still very old school. We don’t just want to release one album a year or something, there’s no point. We had a lot of EP’s. We reckon anytime someone offers us to do something, if we decide to do it, it’s “Yes, OK, we’re ‘gonna send you some tracks because we think that you have something to say and the music you are producing is our interest too.” Otherwise, there’s quite a lot of “Sorry, we’re not ready for your label.” We’re diplomatic enough. We’re just like “Hmm… maybe next time,” or “We are busy.” We love everyone, we understand it’s a struggle. These days, everyone is struggling, you know. There’s no record deal, it’s all about MP3’s and online stuff and Beatport. You know, they’re struggling because people are not actually buying music any more. This is what happened to Rephlex as well. Because of the MP3’s at the time, it was very, very difficult to sell records and make money off music.

How do the two of you compose since you live apart in different cities? Is there one of you who is more into the melodies and the other one more into the rhythm section, for instance?

Fabrizio :: Yes, good question. I never divide whether one is good for producing or arranging the rhythm side and the other one the melody or a similar part of a track. I love to have input in some parts of the melody, I love that. I’d ask Marco “What do you think about this kind of melody?” From one piece to the other, there may be something to change. Too short, too long. And “What do you think about this kind of rhythm or arrangement?” Neither one is better for the melody or the rhythm part. It’s played together. Because we don’t live together, we have two different kinds of studios but with the same synth software, same kind of arrangements. So, step by step, we listen together: “What do you think about this?” “OK, this part and this part… No, cut this part…” So we’re kind of editing together and the very last part is never easy to do.

Marco :: Basically, despite that he does his own work and I do my own, maybe in recent times, I’ve been having more time because I’m a freelancer so I tend to stay home more than him, so I’ve got more time to dedicate to it. I’m very much into software and seeing what’s happening in the music-making world, buying synthesizers, testing out, etc. Then I do something, send it to him and he has a listen, maybe we’ll swap it back. When he does his own stuff, it sounds tremendously equal to what I do, in a way, so, for this, there’s not much difference. This is what Fabrizio wanted to say at the end. Basically, even if he does his own one, has a listen, it sounds like I did it. Maybe I’ll add my own little bit.

[Fabrizio must go and leaves the conversation]

How has your setup evolved over the years? Have you remained faithful to some of the equipment that you’ve kept using since the early days? Did you fully make the switch from synthesizers to software?

Marco :: Like anyone, we started with samplers. At the time we didn’t have a very big setup, because we were not rich. Again, it was a very expensive business. Being in London didn’t help because you count every single penny to pay rent and meals, etc. But we went through the normal digital / analogical kind of recording, sampler, drum machines, combining all together. It was a good element of know-how. At the time, there was no Cubase (a sequencing program – ed.), no PC, it was only that. So you had to sit down in your bedroom, you know, and do your own track. That really helped. But again, I was, like, browsing some magazines at the time and I found out about this new software on PC, which was a tracker, and I remembered the tracker from Pro Tracker on Amiga, like many of my generation. And the name of the tracker, I still remember that, was AXS. It was a Dutch company. And it was the first tracker to offer you two digital oscillators, so no samples. And I was so attracted by this! I decided to order it for us, the very old ordering by post. (laughs) In the end, I bought this Olivetti PC, I think it was an X386. We made one EP only on Engine Records (“Blind Retina” -ed.) That used to be our own label run by Marco Passarani. It was a sub label of it (Final Frontier -ed.) So it was a very interesting experiment. Still today, because I still use that software, by the way. That was our first very first approach to making music using a computer. Since then, Steinberg built the VST trend. The computer was so easy and simple.

You’ve had a longevity of now 30+ years. What overall look do you have on the IDM scene?

Marco :: There’s been so much talking about IDM, especially in the last decade.

Well, as you know, it’s hard to find the right term for it…

Marco :: The term itself, I understand it was actually an invention by someone in Canada because they were promoting a Warp Artificial Intelligence (compilation) CD or something. That was years ago now. You see, our generation knows how difficult it was to digest the “IDM” tag. This is why Rephlex went “Let’s do Braindance.” As far as we’re concerned, it was electronic music. You can box in any kind of music or musical instruments, that’s the concept behind it, but obviously, it wasn’t techno, it wasn’t electro. Okay, it was ambient. For me, it was listening to electronic music with syncopated aggressions and ambient. So, again, you see how difficult it is? And I can consider a new generation being absolutely confused about IDM. Because, as far as I’m concerned, the real IDM might come from Autechre. When I see someone on the tube, as good the track may be, tagged as IDM just because they throw a bunch of samples in a randomized way. Sorry, for me, that is not IDM. For me, It’s just a bunch of samples in a randomized way. That’s difficult because actually—this is a question that popped up from Andrea Benedetti in a forum on Facebook—some American people struggled to understand what IDM could be. And I do say “could be” because still, even I don’t know. If you search for “IDM,” what you hear is a lot of EDM, which is completely different! This is not IDM, that is EDM. These guys, just because it sounds weird… And this is where I get a bit upset. Why should this IDM tag be the “weird” thing? It isn’t. It’s just like melodic techno which is basically what? Trance? Ambient trance? And why not just use ambient trance or just trance? I don’t know.

Right, but whichever term you end up using, Aphex Twin made it somewhat popular for himself in a big way. Much more than, say, Mike Paradinas, Autechre or Plaid. Do you think that there’s a point where the genre could have been more globally popular than it is? And do you think that the current state of the scene nowadays could be improved upon to make it better?

Marco :: Oh yes! Oh, definitely! I think with everyone involved, I think it definitely can be a bigger scene, and a more interesting one. Because we’ve been invaded by this massive electro-house, techno-house, you know, it’s like a blend of everything. And we witnessed it ourselves from the beginning, but like anything, there is an end. But Aphex Twin has always been an icon, something on the side. If you actually carefully listen to him, I’d personally say he’s IDM but he’s not, he’s him. Like Plaid. Plaid have got their own DNA. They’re amazing at making music. And when you listen to Plaid tracks you go like “yeah, it’s good,” because they’ve got their own DNA. So yeah, it could be improved a lot, but unfortunately, it all went a bit down. (laughs)

Lately, you released a lot of previously unreleased music that you’ve made in the 90’s. I bet that you still have a lot to release.

Marco :: Oh Lord, we hope not! (laughs) This is something that was lying on Grant Wilson-Claridge’s hard drive for a long time. And he messaged me and said “Why don’t you get it out?” And I was like “Mmm… I’m not sure.” Because that was a set of tracks that weren’t chosen for this or that. And like anyone, when I listen back to something I did, I’m not keen. I don’t think it was that good. But again, he said “I don’t want it, just release it.” And, like magic, it was one of the best Bandcamp releases we ever had. And I still wonder “Why if you say something, it works, if I say something, it doesn’t work?” This is something I was saying: you need a voice. This electronic scene needs a voice, needs a John Peel. Someone you can recognize as someone who can say “yeah but,” but it’s difficult these days. John Peel is not there anymore, so.

So what can we expect from D’Arcangelo now? What’s in the pipeline?

Marco :: We’re still on our “secret project.” This is something we do just for fun. Actually, we already did. We just released an unpredictable set of tracks with this guy’s name and it went berserk and we received a record deal immediately, and I thought “What the hell?” So, for the next D’Arcangelo, we are working on a different project, and hopefully, it’s going to be our next album after a long time. But we know that things have changed, times are changing, so we don’t expect much except to enjoy ourselves like we always did in releasing whatever. We do it for ourselves. And if you feel pleased to listen, we are pleased.

You have designed some of the covers of your discography and you’ve done Jodey Kendrick’s as well. Do you do that for other artists as well? And do you do your own art on the side? Like exhibits for instance?

Marco :: No, I haven’t done a cover for myself in a long time. I’m always thinking I’d have something ready, but yeah, I’ve got my own job. I do 3D for companies but that’s another story. Sometimes, Jodey Kendrick comes to me like “Can you do this?” And you know, I go “OK, I’ll do something about it.”(laughs) It’s like a joint venture. It’s just fun, really. And I appreciate that he likes what I do because, you know, Jodey is the one who throws the actual stone, Grant is the one who grabs it, and is like “OK, you can work this way” and then passes it on to me and I have to visualize the idea, which is okay, it’s fun. So I’m quite glad that, so far, it’s working. Jodey’s an amazing person. Last time I saw him in person was a long time ago in Devon, we had one of the last Rephlex gigs together. And it was pure fun. So, since then, we always promised ourselves to meet and gather and have some drinks until we die, basically. But then the pandemic came to disrupt everything, so possibly next year, but then the good news is, he’s doing good and I’m happy about it.

You’re opening for Aphex Twin in Verona next weekend. This must obviously be a special moment that you’re looking forward to, especially since it’s taking place in Italy.

Marco :: It is! It was totally unexpected! When I received the message, it was like, “What?” and I must say it’s like it’s ‘gonna be the first time playing a gig in my life. I don’t know why I’m so tense, because we’ve played at the same gig with Richard a lot of times, you know that, but this time is slightly different because he’s giving us an incredible window. And obviously, you know, I’m grateful for this, and I hope I’m ‘gonna say thank you in person next Friday July 14, 2023.

D’Arcangelo

Discogs | Facebook | Bandcamp | Bandcamp Suction | Soundcloud