Compared to Grischa Lichtenberger’s previous efforts, 1224_28_lv_1_re obliteration—released by South Korean label dingn\dents at the extreme tail end of 2024—leans even further into the digital noise side of glitch.

Phantoms of sounds

Compared to Grischa Lichtenberger’s previous efforts, 1224_28_lv_1_re obliteration—released by South Korean label dingn\dents at the extreme tail end of 2024—leans even further into the digital noise side of glitch. This is especially evident after Works for Last Work, out on Raster in 2023, an excellent and much more ambient soundtrack to the Batsheva Dance Company’s Last Work. If Works for Last Work understandably focussed on the fluid dancing of a biological entity, now the focus is on the (erroneous, hitchy) movement of a machine: the first quarter of the album’s runtime is occupied by an unrelenting barrage of hard clicks, pops and assorted glitches, clean to the point of sterility, visualized in the accompanying video by a series of dashes, 0s, and misc Unicode symbols, monospace white on black.

When the track finally opens up to a ghastly, reverb-heavy soundscape, the contrast is palpable, and we’re left with a much emptier space to cope with. The image also changes, to a morphing, shaded, light blue drawing of something between pulsating stars and metallic walls, a terminal degeneration of Gantz Graf. Soon enough the mechanical aggression seeps back in the form of some engine desperately trying to start and inject some energy into the system and overtake its human developer.

Divided into movements ::

“obliteration” is clearly divided into movements, which sometimes feed into each other and others are separated by short silences. The sound palette is minimal and made up of textures that seem irreconcilable but end up working without feeling abrupt or strident—until they do, of course. The choice to present this album as a single uninterrupted mechanism is interesting: like its press release, the album is a disjointed narrative where I stare at the cursor trudging forward but remain at a loss to interpret the events. And like its press release and this review, “obliteration” oscillates between a dejected “we” trying to shore the ruins of its past and an “I” selfishly accumulating facets and fragments of subjective interpretation and sentiment. But any subject is its own centre and can at best reach for and strike down on itself, “with a lethargy and boredom that seeps out of every pore, drowned out by the ever-growing roar of what’s been missed.” After all, “we plan nothing revolutionary, nothing stirring or inventive, neither in garages nor in basements.”

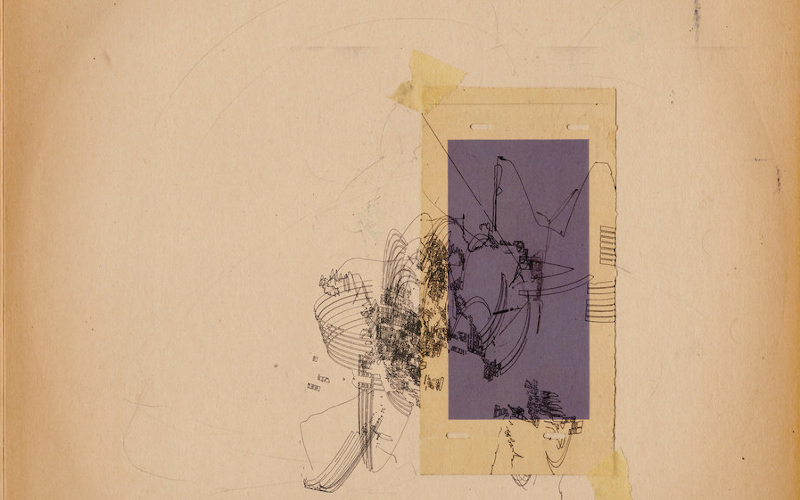

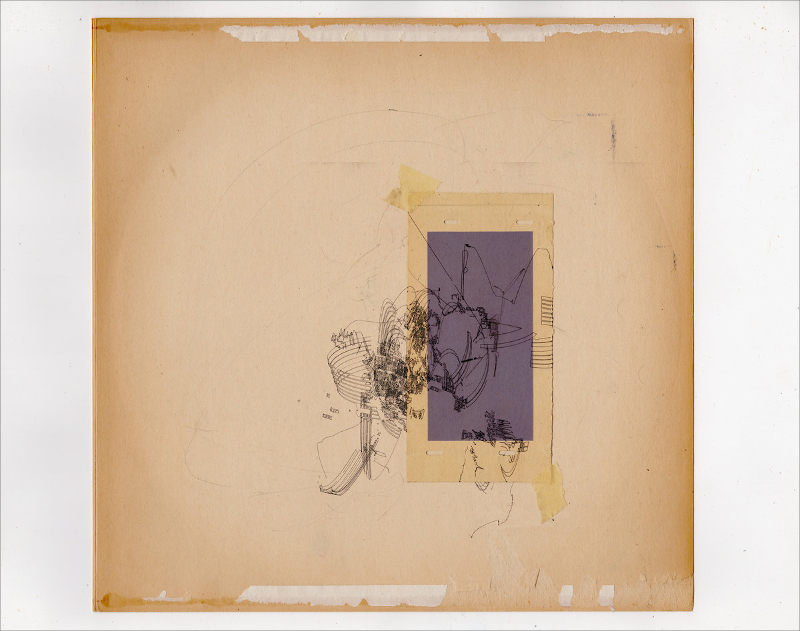

I see phantoms of sounds that might not actually be there. My devices (my DAC and headphones, my ears clogged by a cold) cause the faintest of distortions that I will never be able to tease apart from the actual reality of the composition. Rather than filling in the gaps intuitively, I hyperfixate on them: “I don’t flee to paradise but to the miserable game of affirming pale, hollow self-awareness.” The phantoms of a hand and a face appear on the sides of a flickering Rothkian rectangle of blues and blacks in the last portion of the track and video—a droney and drugged out reprise of the first theme, perhaps—but they do not act on the quivering shape. They observe it and touch it, without changing its course. “We plan nothing revolutionary, nothing stirring or inventive, neither in garages nor in basements.”

The text of 1224_19_lv_1_re obliteration mentions Thomas Midgley, a man whose “instinct for the regrettable was almost uncanny” (as remarked by Bill Bryson). The engineer, left disabled by polio, devised a contraption of ropes and pulleys to still be able to move around his dwelling. He was found dead by strangulation, trapped by his invention. The device had become the subject.

1224_28_lv_1_re obliteration is available on dingn\dents. [Bandcamp]

![Squaric :: 808 [Remixes] (Diffuse Reality) — [concise]](https://igloomag.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/squaric-808-remixes_feat-75x75.jpg)