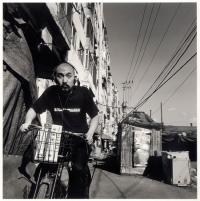

(06.17.05) An apostle of analog: resistors and rheostats, Rhodes pianos, the turntable, the microphone, Mellotron and Moog. Mojave is all that and a bag of beats.

I first met him at the Hongdae market where he was selling copies of his latest CD, 19th Century Comet, which was playing from a little stereo beside him. My friend and I stopped to listen once, stopped twice. The third time we each bought a copy. The next day I e-mailed him to find out who this guy was behind the beautiful, haunting tracks.

A few weeks later we met up at a coffee shop in downtown Seoul. Wearing his black Moog t-shirt, shaved head shining, looking like a monk from outer space, Mojave led me upstairs to a small table littered with ashes. A half-smoked pack of squares sat near an empty coffee cup. He apologized for the cigarettes. That was the first thing he said to me:

“I’m sorry I smoke so much.”

You don’t meet many nice people in the music business.

We sat down. He smoked and I scribbled. Over the next few hours it became clear to me I was talking with somebody serious, someone for real. This was a man who wasn’t in it part-time, or for the allure of fame and all that can come with it. This was a 24/7, straight-up, straight down the line guy when it came to who he was, and what he wanted to do.

“If there’s one thing I want people to know, it’s why I make this kind of music.”

We had been talking about the relative unpopularity of electronic music, both in Korea and internationally.

“Maybe not everyone listens to Mojave,” he continued, a half-cigarette lying between his delicate fingers, “I hope more people listen to my music and enjoy. But what’s most important is I did the right thing.”

To Mojave, doing the right thing means staying true to the sounds he feels, hears inside. I asked him to describe this process.

“I sit on the floor in my room and turn on the tape machine. Using small analog synthesizers to generate noises, I put it through an old amp, sampling and cataloguing these sounds.”

Noise. That’s what he calls the material he works with: he manipulates noise.

“Melody doesn’t matter. Timbre develops the melody, the beginning and end of the music comes from mistakes and accidents.”

Like a painter who utilizes an unwanted brush stroke to develop the new image or theme for his picture, Mojave believes in those happy accidents that lead to unexpected developments.

“The inspiration is always there, and I find it by chance using electronic instruments.”

And it seems Mojave may have accidentally been born into this line of work. His father, a retired career soldier, traded a reel-to-reel tape deck to pay for his son’s delivery.

“It was an Akai 1710. For some reason, my mother remembered the make and model, although my father didn’t. I think he got it on the American black market while he was serving in Vietnam. I have always wanted to get one like it.”

I tell him it reminds me of the proverbial bluesman who sold his soul at the crossroads. His story seems more fitting for an electronic age where mythological beasts and the notion of a soul have been traded for machines and chaos theories.

Background ::

Mojave was born January of 1972. His family moved around a lot, following his father from base to base. A child of the eighties, he grew up listening to 80’s new wave synth-pop like Depeche Mode, Thomas Dolby, Human League, The Buggles, OMD, Tears for Fears, and New Order. When he was in middle-school, another of those beautiful accidents occurred.

“After school, as always, I was turning on my beloved old hi-fi and was listening and tuning FM radio on a peaceful evening. I heard some live broadcast from a European electronic music festival. The music was filled with very organic and abstract electronic noises, mangled human voices, strange melodies that I had never heard. I was blown away.”

Thus began the second birth or the metamorphosis of Mingyu the boy into Mojave the man.

Later, when he was a teenager, his father bought him a boom-box with dual cassettes so he could tape himself speaking in order to practice English.

“English class was just a boring time to kill for most kids. My real interest in the double deck was on another side. It was the middle of the 1980s. I was a fanatic pop kid, an enthusiastic maniac for Casey Kasem’s weekly American Top 40 broadcasts. I began to do remixes of them in my own ways. I played the original tape in the A deck, and recorded excerpted certain parts to the B deck . . . the beginning of my musical career,” he says with a wide smile.

His father, unknowingly, provided him with the first tools of his trade. However, he was not always the biggest supporter of his son’s budding interests.

“He did allow  me to take piano lessons when I was young. But it was my mother who was always on my side. She is my mental support. But they both want me to have success.”

me to take piano lessons when I was young. But it was my mother who was always on my side. She is my mental support. But they both want me to have success.”

Success is elusive, and not just because it is a difficult plateau to reach. For many, if not most, defining success is a difficult task.

“I live at home so I can make music. I lost everything to continue my musical career. My father always asks ‘where is the money?’ and then the worst part is over.”

The conversation drifts to influences and theory. We talk about artists such as Squarepusher, Beck, Oval, Autechre, and Giorgio Moroder. Then the zen-meister of music, John Cage, inevitably creeps into the flow of thoughts. Mojave talks about how he was deeply moved by Cage’s composition/performance, “4’33,” where a piano player takes his place at the piano and plays nothing for the next four minutes and thirty three seconds, forcing the audience to experience silence, and the sounds created by the audience themselves.

“Not generating sound is as important as generating sound,” he tells me. “And when you’re generating sound, organizing the silence is important.”

So silence defines non-silence. This seems an extremely important concept for him. And out of that silence emerges the “noises from old tape machines, mikes, turntables.” This is what he organizes: the blips, bleeps, and whirs from these antiquated devices.

Several times during our discussion the use of these types of analog equipment has cropped up. I ask him why he has such a disdain for the digital format where his music is destined to find itself.

“Analog is not perfect. And it allows for the paradox – the sound is perfect because it inspires images and melodies, but analog equipment is imprecise. Also, you can touch analog equipment; I don’t like digital instruments because there is too much distance.”

He also thinks today’s audio is cold.

“You can’t surpass digital technology, but the key is the source. If the source is warm, the recording is warm.”

I still want to know exactly how he gets this warmer sound across to a digital recording, such as a CD.

“First of all, I use a certain tube-based amp. I also record everything more than once. The sounds go on my computer; then I re-record it by playing it through speakers into microphones.”

By this time, he’s smoked nearly his whole pack of cigarettes and the coffee cups are empty. It seems like the time to ask him my last question. Where did he get the name Mojave?

“I saw this movie,” he says. “It had a scene about the  Mojave desert. I saw that emptiness, the void of the desert was very dramatic and inspiring – like a white sketch book. Then, when I was a college student, I wrote a fan letter to Steve Roach. He was living near the Mojave at the time. He replied to me, and sent me some of his albums. I was so happy about that.”

Mojave desert. I saw that emptiness, the void of the desert was very dramatic and inspiring – like a white sketch book. Then, when I was a college student, I wrote a fan letter to Steve Roach. He was living near the Mojave at the time. He replied to me, and sent me some of his albums. I was so happy about that.”

So that’s the story of Mojave. A man who makes noise with machines. And with the spaces between the notes, where there is nothing but nothing. Except those vast plains of silence.

You can buy Mojave merchandise through his website: www.utput.net

![Pole :: Tempus Remixes (Mute) — [concise]](https://igloomag.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/pole-tempus-remixes_feat-75x75.jpg)

![Hasbeen :: Bunker Symphonies II (Clean Error) — [concise]](https://igloomag.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2025/04/hasbeen-bunker-symphonies-ii_feat-75x75.jpg)