A memorable snapshot of an era which many longtime Warp aficionados think of fondly as representing the very pinnacle of the label’s musical prowess, and for anyone wishing to delve further into Warp’s back catalog, a handy list of every WAP (singles and EPs with catalog numbers from 1 to 99) and WARP (albums with catalog numbers from 1 to 55) release up to that time was included inside the compilation‘s CD booklet.

Weird And Radical Projects

Where to begin with We Are Reasonable People? Well, for starters, perhaps with the title of the compilation itself. It is, as may or may not be readily apparent at first glance, an interpretation of the acronym “W.A.R.P.,” or in other words, the name of the seminal British label who issued this collection. To the best of this writer’s knowledge, the backronym (a term which according to the Oxford English Dictionary means “an acronym deliberately formed from a phrase whose initial letters spell out a particular word or words, either to create a memorable name or as a fanciful explanation of a word’s origin.”) We Are Reasonable People originated around late 1995 or early 1996, initially appearing on flyers designed by Ian Anderson, best known as the mastermind behind The Designers Republic, the graphic design studio which has been strongly associated with Warp’s visual identity from the label’s very inception, and was responsible for designing the famous purple sleeves in which its 12” singles were packaged as a way to stand out amidst countless thousands of anonymous white label vinyl releases, and for creating the artwork for such legendary Warp releases as Autechre’s Tri Repetae, LFO’s Frequencies, and Nightmares On Wax’s A Word Of Science.

The aforementioned flyers were distributed to potential partygoers in order to promote the “Blech” club night which the fine folks behind the Warp label held on the second Saturday of every month at the Sheffield University Student Union’s Raynor Lounge, although “Blech” originated with the cassette tape issued by the label in December of 1995, which bore that name, and contained a mix comprised solely of tracks by artists from the Warp roster made by PC & Strictly Kev, better known as DJ Food of the Ninja Tune label fame (another similarly-minded mix, also helmed by PC & Strictly Kev, and entitled Blech II: Blechsdöttir, was released on CD in September of 1996, and many years later, Strictly Kev issued two continuations of the series, Blech 20.1, and Blech 20.2, released as part of Warp’s 20th anniversary celebrations in December of 2009 and February of 2010, respectively, and made available, in a sign of changing music distribution models, as free MP3 downloads available via the DJ Food Soundcloud account).

In actual fact, however, the term Warp was initially expanded upon to mean “Weird And Radical Projects,” although that too is backronym, as it was coined after the name of the label had already been established, though it should be observed that the imprint’s original name was Warped Records, but because it was difficult to distinguish from the word “Warp” over the telephone, the label’s founders ultimately decided to settle on the name we all now know and love. Returning for a brief spell to the backronym of “Weird And Radical Projects,” however, let that be the starting point for this deep dive of a retrospective review, because issuing music that may well be considered both weird as well as radical, is precisely what Warp has excelled at as a label, and the very compilation in question is proof positive of that assertion.

The originally Sheffield-based Warp established itself within the world of contemporary electronic music as a true force to be reckoned with thanks to the highly influential and groundbreaking two compilations in the “Artificial Intelligence” series bookended by two compilations released in 1992 and 1994 respectively, the first volume of which celebrated its 30th anniversary in 2022 with a long-awaited vinyl repress, and which single-handedly popularized the then nascent and contentious genre term of “intelligent dance music,” or IDM for short, dismissed by many of the artists associated with it as essentially patently ridiculous, none more so than Warp stalwart Aphex Twin himself, who was cited in a 1997 interview as saying: “I just think it’s really funny to have terms like that. It’s basically saying ‘this is intelligent and everything else is stupid.’ It’s really nasty to everyone else’s music. (laughs) It makes me laugh, things like that. I don’t use names. I just say that I like something or I don’t.” Nevertheless, for better or ill, the term very much stuck, in spite of Warp’s own effort to brand the AI series of releases with the genre tag of “electronic listening music,” or the stylistically-adjacent Aphex Twin-co-owned Rephlex label’s own coinage of “braindance.”

In spite of what Cardi B and Megan Thee Stallion may have you believe these days, Warp was first on the scene with the acronym “WAP,” albeit one with a very different meaning to moist naughty bits, and it wasn’t so much an acronym, as a prefix used by the label along with an appropriate release number to denote a single or an extended play in its catalog of both vinyl and CD releases, so that, for instance, Warp’s very first single, Forgemasters’ Track With No Name, issued in 1991 on 12” vinyl, bore the catalog number “WAP 1,” whereas the label’s album-length offerings bear the prefix WARP followed by either CD or LP, depending on the format and the appropriate release number, and thus, for example, the very first album issued by the label, although technically more of an EP, but nonetheless the longest release Warp had put out up until that time, Sweet Exorcist’s Clonk’s Coming from 1991, had the catalog number of either “WARP CD1” for the compact disc, or “WARP LP1″ for the 12” vinyl.

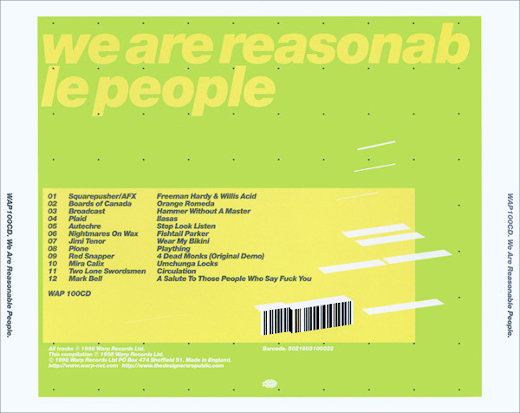

To this end, the catalog number attached to We Are Reasonable People, “WAP100,” denoted Warp’s 100th single/extended play release, albeit being a release celebrating this significant milestone in the label’s history, it took the form of a full-length compilation released on the 29th of June, 1998—just a year shy of Warp’s 10 year anniversary, which merited its own celebrations—in both CD and 3×12″ formats, and presented its listeners with a track list featuring a veritable who’s who of Warp’s roster at that particular point in time. As such, it offered a memorable snapshot of an era which many longtime Warp aficionados think of fondly as representing the very pinnacle of the label’s musical prowess, and for anyone wishing to delve further into Warp’s back catalog, a handy list of every WAP (singles and EPs with catalog numbers from 1 to 99) and WARP (albums with catalog numbers from 1 to 55) release up to that time was included inside the compilation’s CD booklet.

“A memorable snapshot of an era which many longtime Warp aficionados think of fondly as representing the very pinnacle of the label’s musical prowess, and for anyone wishing to delve further into Warp’s back catalog.” ~Roman W.

For listeners in the U.S. and Canada, “WAP100” wasn’t easy to come by at the time of its release, and in those select few North American record stores that did actually carry it, it was available as a pricey UK import. This regrettable state of affairs was due to the fact that at that point in time Warp had yet to establish its first stateside office, which wouldn’t happen until around the year 2000. Prior to Warp eventually opening up its base of North American operations in New York, the label’s select few releases were licensed on that continent to labels such as Warner Bros. subsidiary Sire, who issued a number of Aphex Twin releases such as Selected Ambient Works Volume II, …I Care Because You Do, and the Richard D. James Album, the Chicago industrial imprint Wax Trax! who released Autechre’s Amber, Tri Repetae, and Nightmares On Wax’s Smokers Delight albums, among others, as well as Trent Reznor’s Nothing Records, who issued Autechre’s LP5 and EP7, Plaid’s Not For Threes, Rest Proof Clockwork and Squarepusher’s Music Is Rotted One Note, and Selection Sixteen, plus a handful of others, and the indie rock powerhouse Matador, who licensed such full-lengths as Boards Of Canada’s seminal debut Music Has The Right To Children, Red Snapper’s Making Bones, Two Lone Swordsmen’s Stay Down, and Plone’s For Beginner Piano.

For those such as this writer, who in the 1990s was living in Canada, for whom access to the Warp catalog was difficult to gain due to a lack of North American distribution for a lot of the label’s output, but who were nonetheless willing enough to part with their hard-earned cash in order to purchase an expensive import and curious enough to more or less blindly invest in a series of tracks that back in the pre-streaming day of 1998, they usually had no way of previewing prior to buying the CD or vinyl, “WAP100” no doubt offered a welcome surprise when it came to the general high quality of the compilation’s auditory content.

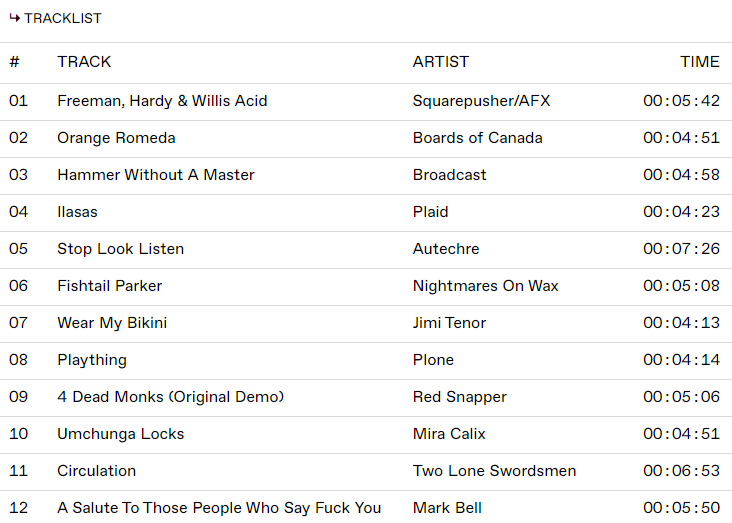

But enough with background trivia. What We Are Reasonable People is ultimately about is the music itself, so let us take a closer look, or perhaps more appropriately, a closer listen to what is on offer here, as there is truly plenty to feast one’s ears upon—12 different artists from Warp’s then-roster serve up 12 tracks, all of which are entirely exclusive to this release. The compilation opens with a genuine bang by virtue of the only officially released collaboration between two titans of a uniquely IDM-infused take on jungle and drum & bass which has come to be known as drill & bass, namely the meeting of two great musical minds of Tom Jenkinson and Richard D. James, better known to us under their respective aliases of Squarepusher and Aphex Twin (appearing here under the AFX moniker), the latter of whom was Jenkinson’s mentor of sorts as well as the man who more or less discovered his talents and brought him to the attention of the wider world by releasing Squarepusher’s classic debut full-length Feed Me Weird Things on his own Rephlex label in 1996.

The opening salvo, entitled “Freeman Hardy & Willis Acid,” so as to further emphasize the collaborative nature of this musical endeavor is a spectacular blend of the two artists’ stylistic sensibilities, featuring the sort of frenetic, finely sliced and diced junglist breakbeats which characterize so much of both Squarepusher’s and Aphex Twin’s output, and underpinned by ambient synth pads taken wholesale from the Selected Ambient Works Volume II playbook, and morphing for an all too brief final minute of its 5 minute 42 seconds runtime into the sort of righteous TB-303 acid squelcher which Aphex is known to whip out from his vast arsenal of musical tricks every now and again. As good as this track is, it ultimately leaves one longing for an album-length collaboration from this dynamic IDM duo—one which unfortunately appears unlikely to happen, unless of course, as a cursory YouTube search seems to reveal, there is actually more of where this seemingly uniquely one-off gem came from in the Squarepusher/AFX archives, which may yet see the light of day on the occasion of yet another of James’ sporadic Soundcloud dumps of unreleased material.

The second track is a trip down memory lane carrying the listener on the wings of borrowed nostalgia for the unremembered (at least for those of us born from 1980 onwards) 1970s, by virtue of a sound world which conjures up the ear’s National Film Board Of Canada (or NFB, for short) nature documentary soundtracks and the wide eyed naiveté of that decade’s children’s television programs, courtesy of the NFB-indebted—in both name and sound—duo of Boards Of Canada, comprised of the Scottish siblings Mike and Marcus Sandison, who following the self-released Twoism 12” extended play on their own Music70 imprint, limited to a mere 100 copies at the time of its initial release, and which garnered the praise of Autechre’s Sean Booth, who brought it to the attention of the proprietor of the venerable Manchester-based electronic label Skam, on whom a bit more further on in this review, made their official recording debut in 1996 with the stellar Hi Scores EP on the said imprint.

Back in the summer of 1998, however, the Sandisons, who at the time didn’t yet acknowledge to the wider world that they were actually brothers, fearing undue comparison to other electronic sibling outfits such Orbital helmed by brothers Paul and Phil Hartnoll, were hot on the heels of their now-canonical debut full-length album Music Has The Right To Children released just over a month prior to the We Are Reasonable People compilation. Indeed, the tune in question, entitled “Orange Romeda” (and it’s worth pointing out here that as any avid listener of the BOC track “Aquarius” can tell you, the color orange has become somewhat synonymous with the band, although it’s anyone’s guess as to what a “romeda” is), could very easily sit alongside any of the other 17 tracks comprising BOC’s inaugural LP-length offering, and evidently sounds like it must’ve come into being during the same recording sessions which birthed the material on their official debut album.

All the hallmarks of late 1990s BOC are very much present and correct on this tune, including a strong melodic sensibility influenced by countless unacknowledged nameless creators of synth-driven library music which illustrated many a nature doc and public service announcement in the 70s, hip-hop-inspired beats, as well as samples of children’s voices for that extra nostalgic touch which makes one year for the innocence of an irretrievably lost childhood—in this case, brought to you by a vocal snippet sourced from a Sesame Street episode in which a group of kids, along with Big Bird, Snuffleupagus, and the Word Fairy, say the word “Fly!” As such, “Orange Romeda” stands among some of the best tracks in BOC’s entire catalog, and it serves as one of the major highlights of this compilation.

Next up is an offering by Broadcast, a group originating from Birmingham, and led by the vocalist Trish Keenan and bassist James Cargill along with a revolving cast of guitarists, drummers and keyboard players. Although presently Broadcast is acknowledged as one of the key acts which helped cement Warp’s legacy as an adventurous label willing to expand its boundaries beyond the confines of strictly electronic sounds, its presence on the label’s roster was initially regarded as somewhat controversial at the time, given that, along with Jimi Tenor and Red Snapper, both of whom also makes an appearance on We Are Reasonable People, they were the only acts signed to Warp during that period to prominently feature vocals in their repertoire and use live instruments alongside more overtly electronic flourishes. The track in question, “Hammer Without A Master,” however, is the rare Broadcast tune which is entirely instrumental, and while it is underpinned by vigorous live drumming, the other elements it is comprised of, such as organ-imitating keyboards and all manner of curious electronically processed sounds, make Broadcast’s considerable and readily acknowledged debt to the BBC Radiophonic Workshop’s pioneering experimentation in the field of contemporary electronic music quite apparent.

Broadcast’s inclusion on We Are Reasonable People is notable for the fact, that at the time of the compilation’s release, the group had only had a single release on Warp to their name, an album-length compilation from 1997 entitled Work And Non Work comprised of early singles and EPs issued on such cult labels as Stereolab’s Duophonic Super 45s and Wurlitzer Jukebox, and their debut album proper, The Noise Made By People, wouldn’t arrive until the year 2000. The group would continue to release with Warp, issuing a number of warmly received albums now regarded as bona fide classics, until it met an untimely end following Trish Keenan’s sudden and tragic passing from pneumonia in January of 2011, shortly after the singer had contracted swine flu while completing Broadcast’s tour of Australia. The band’s towering presence as a much revered cult Warp legacy act, and its subsequent painfully felt absence, is perhaps best exemplified by the fact that since its unexpected demise, there has been a string of archival releases from the group’s vaults, and 2024 alone will see Warp issuing two collections of demo recordings from the years 2000-2009, Spell Blanket and Distant Call, respectively, which are reported to be the final two releases from the group.

The fourth track in the compilation’s running order is “Ilasas” by Warp stalwarts Plaid, the duo of Ed Handley and Andy Turner who started recording under that alias whilst still being members of the electronic trio The Black Dog, along with their then-bandmate Ken Downie, issuing their debut album under the Plaid guise, Mbuki Mvuki in 1991 on their own Black Dog Productions label. The Black Dog’s own history traces back to 1989, and they are widely regarded as one of the pioneers of the IDM genre, from a time before that even became a term, with their uniquely British take on chiefly American genres such as Detroit techno, electro and breakbeat, and they have also been strongly associated with Warp’s own legacy, releasing two classic albums with the label, the first of which, Bytes, under the umbrella project name of Black Dog Productions, was issued as part of the label’s seminal and genre-defining Artificial Intelligence series and was essentially a compilation of both solo and collaborative tracks by all three of The Black Dog collective’s members, under such assorted aliases as Close Up Over (Ed Handley), Atypic (Andy Turner), Discordian Popes (Ken Downie), and the aforementioned Plaid (Ed Handley and Andy Turner), among others.

In 1995 Ed Handley and Andy Turner decided to end their six year association with Ken Downie, who decided to continue on with The Black Dog moniker, and thereafter focused strictly on Plaid as their main musical vehicle, going on to release their sophomore album, and their full-length Warp debut as a duo, Not For Threes, in 1997, and continuing to remain with the label until this very day. If there is one key element of the overall Plaid sound, it most certainly has to be the fact that most, if not all, of their compositions tend to be highly melodic in nature, and often feature overlapping, complementary counterpoint melodies which frequently tend to have a certain joyful playfulness about them, and are usually set over either chopped up breakbeats or the sort of intricately programmed and usually non-repetitive rhythms which have become the hallmark of IDM. In this regard, “Ilasas” does not disappoint in the least, serving up a hearty helping of all of the aforementioned aspects which define Plaid’s unique take on contemporary British electronic music.

Much of the same can be said about the next track in sequence, “Stop Look Listen” by the electronic duo of Sean Booth and Rob Brown, better known under the alias of Autechre, formed in 1987 in Rochdale, Greater Manchester, and who made their Warp debut in 1992 courtesy of the first “Artificial Intelligence” compilation, issuing their debut album as part of that series the following year, and continuing up until the present day to release all of their subsequent albums and EPs with the label whose musical legacy that very group has in no small measure helped to establish. In many regards, Autechre’s contribution to the We Are Reasonable People compilation can be seen as somewhat of an outlier in the group’s oeuvre, signifying an end of an era defined by a greater melodic sensibility, as from that point onward, much to the dismay of many of their early fans, and to the delight of those among them who value the group’s ceaseless striving for continual artistic growth and can appreciate a more avant-garde approach to sound manipulation, Autechre’s music would grow increasingly more abstract, occasionally abrasive and ever more experimental with each subsequent album, with far less attention being paid to any sort of obviously melodic lines, and far more consideration given to highly complex polyrhythms which don’t easily lend themselves to dancing.

This tireless devotion to perpetually reinventing their sound with each release has cemented Autechre’s status as an act commanding much respect and admiration from both critics, fans and fellow music producers alike for being on the very cutting edge of stylistic innovation. “Stop Look Listen” is the rare Autechre track to actually feature an easily pronounceable title which uses actual terms found in the English language, given that the vast majority of their song titles tend to be difficult to properly pronounce words such as “Cipater,” “Eidetic Casein,” or “P.:NTIL,” which have been entirely made up by the duo themselves without much in the way of meaning, for the express purpose, as they themselves have stated, of tracks simply needing some sort of a name, and not much else.

“Stop Look Listen” is also a tune that is, well, rather unusually tuneful, particularly by the standards of latter day Autechre, with potentially hummable melodies aplenty and even a synth which sounds not unlike a Fender Rhodes piano with the vibrato effect turned all the way up, and is as close as the duo has ever come to using anything in the way of traditional instrumentation. The mechanical rhythms on which the song rests, on the other hand, are made up of tinny, metallic-sounding, and obviously digitally generated slivers of sound of the sort which characterized their self-titled album, commonly referred to as LP5, by virtue of being Autechre’s fifth full-length, which Warp released a mere two weeks after “WAP100,” and from which by all appearances “Stop Look Listen” seems to be an outtake—one which simply wouldn’t fit all that comfortably alongside the other tracks comprising that LP, due to it being perhaps a little too melodic.

“Fishtail Parker,” the sixth track on We Are Reasonable People comes courtesy of the longest serving act on Warp’s roster to this very day, Nightmares On Wax, originally founded in 1988 as the duo of George “DJ E.A.S.E.” Evelyn, the group’s sole permanent member, and Kevin “Boywonder” Harper, and debuting only a year later with Warp’s second ever release bearing the catalog number of “WAP 2,” the single “Dextrous,” created in the style of what was at that time the label’s initial stock in trade, bleep techno, a regional dance music subgenre which developed in Northern England towards the tail end of the 1980s and was defined by minimalist, electro-influenced synth tones (the titular “bleeps”), weighty, dub-inspired sub-bass and repetitive rhythms stylized after American house and techno music. NOW’s debut album, entitled A Word Of Science (The 1st & Final Chapter), arrived in 1991 and proved to be exactly what it said on the tin, namely that it proved to be simultaneously a beginning and an ending of sorts, in that it was the only album recorded while they were still a duo, and the sole LP of theirs which was primarily a dance record, musically influenced principally by such styles as electro, house, techno and acid, with a hearty helping of soul mixed in for good measure. From the sophomore album Smokers Delight onwards, however, once the project became the sole provenance of George Evelyn (albeit with regular contributions from Robin Taylor-Firth), NOW’s sound became firmly rooted in hip-hop, and perhaps even more so in its more laid back, stoner- friendly British cousin, trip hop, and the various strands of downtempo which stemmed from it. To this end, for a time NOW became one of Warp’s most conventional-sounding acts, shying away from the sort of boundary-pushing sonic experimentation labelmates such as Autechre and Aphex Twin have accustomed their listeners to, in favor of sounds that are far easier on the ears and more conductive to head nodding, than to chin-stroking.

It should come as no surprise, therefore, that the NOW song in question is the least remarkable, and most ordinary-sounding out of the compilation’s eleven tracks, and as such can be regarded as its weakest link, but even so, it is perfectly enjoyable all the same in its amiable, jolly, happy-go-lucky up-tempo pleasantness—the sort of tune one might wish to listen to on a particularly sunny summer day, preferably on a tropical seaside beach somewhere, with a margarita in hand—and that’s precisely what Nightmares On Wax’ easygoing charm is about—music that doesn’t necessarily aim to challenge the listener’s perceptions of what is possible within the realm of electronic sounds, but rather intends for them to kick back in their favorite easy chair with a fat ass joint (as the title of NOW’s aforementioned boom bap hip hop-inspired classic Smokers Delight clearly suggests) and chill out to some largely undemanding downtempo grooves.

Next up in the compilation’s sequence is “Wear My Bikini” by Jimi Tenor, the chosen artistic alias of Finnish musician Lassi Lehto, who made his recording debut in 1994 with the album Sähkömies originally issued by the equally Finnish imprint Puu, a Jimi Tenor-operated sublabel of Sähkö Recordings, a label established by Tommi Grönlund and the late Mika Vainio of the famed Finnish electronic duo Pan Sonic. In the second half of the 1990’s, Tenor would go on to sign with Warp Records, a relationship which commenced with his third full-length outing, Intervision, which saw the light of day in 1997, and culminated with his fifth LP, Out Of Nowhere, released in the year 2000, but also involved Warp reissuing his first two albums, which had previously been available only in Finland. In many respects, Jimi Tenor was somewhat of a square peg in a round hole when it came to being part of Warp’s roster in the mid-1990s, in that both him and Broadcast, who signed to the label at roughly the same time, were virtually the only Warp acts at the time to regularly feature vocals combined with live instrumentation, years before artists who employed similar tactics, albeit to somewhat different ends, such as the neo-soul crooner Jamie Lidell and indie rockers Maxïmo Park, came onboard the Warp ship. Jimi Tenor, a multi-instrumentalist who among his many musical chops counted playing both baritone and tenor saxophone, as well as the flute and keyboards, offered an intriguing blend of future jazz, funk, soul and house music practically unlike any other artist on Warp’s roster at the time, bar perhaps some more outré moments of the aforementioned Nightmares On Wax and perhaps Red Snapper, about whom a bit more later.

“Wear My Bikini,” a groovy up-tempo number anchored by a funky bassline, a jazzy sax lead and a squiggly synth melody, and the lone track on We Are Reasonable People to feature singing, is very much classic Jimi Tenor fare, and comes equipped with a quirky dose of humor to boot, which, granted, may not be to everyone’s liking, what with Tenor repeating the lines “I eat dollar hot dogs, like I wear my bikini” time and again throughout the song, which to all appearances seems to be sung by him in very much a tongue-firmly-in-cheek sort of way. It may rankle the ears of those listeners who prefer Warp’s more electronically-minded instrumental fare, and one would be hard pressed not to admit that the track does seem to stick out on “WAP100” like a proverbial sore thumb, but it should strike just about everyone else as simply no more and no less than a very fun little tune, and one to the sounds of which it’s entirely possible to bust a few vigorous dance moves, if it ever came on the stereo during a particularly lively house party.

The eighth track comes courtesy of Plone, an act, which began life in Birmingham all the way back in late 1994, and comprised initially of Mark Cancellara and Michael Johnston, but soon thereafter evolved into a trio, once Johnston’s then-housemate, Mike “Billy” Bainbridge joined the outfit. The group’s name is an entirely imaginary word purported to sound like a cartoon ricochet, and this etymology speaks volumes of their actual music, which can indeed be described as akin to the sort of soundtracks one may recall gracing many a vintage cartoon and other sorts of children’s television programming, but is equally indebted to classic library music of the 1960’s and 70’s, as well as the pioneering electronic efforts of the BBC Radiophonic workshop, which is one of several things Plone shared in common with their label-mates, fellow Brummies and personal friends Broadcast, whom in 1996, prior to either of the acts releasing anything with Warp, Plone has supported in concert. It may very well have been that association with Broadcast which brought them to the attention of Rob Mitchell, who along with Steve Beckett co-founded Warp Records, and was responsible for signing Plone to the label. Before that happened, however, Plone made its official recording debut with the 7” vinyl-only single entitled Press A Key, which was issued in 1997 on the cult indie label Wurlitzer Jukebox, who perhaps not coincidentally also released Broadcast’s debut 7” single, Accidentals, only a year earlier.

Plone’s contribution to “WAP100,” the very aptly titled track “Plaything,” marked the trio’s Warp debut, and offers an excellent introduction to the group’s highly playful and incredibly melodic sound which borders on just the right side of saccharine and vintage muzak kitsch, which is precisely what the track in question may accurately be described as, seeing as it offers the sort of joyfully whimsical sonic aesthetic which is rarely to be found among Plone’s Warp contemporaries, and is perhaps only matched somewhat by Plaid’s more cheery moments. The We Are Reasonable People exclusive was followed in September of 1998 by Plone’s debut three-track single as a Warp act, Plock, which alongside two single-only b-sides featured the titular song, also included on their debut album For Beginner Piano released concurrently in the same month, with both the single and the LP expanding upon Plone’s jolly sound to take in such influences as the soundtrack work of John Barry and Ennio Morricone, the good vibrations of the Beach Boys and the soundworld of ’60s synth pioneers Perrey & Kingsley.

The singular sound world created on that album shared a certain retro-fixated kinship with AIR’s bestselling breakout debut Moon Safari, and who knows, perhaps had Warp invested more resources in promoting Plone’s music, the group may well have wound up basking in the sort of wide-scale success on par with that enjoyed by the aforementioned French duo. Unfortunately for Birmingham trio, however, whilst a follow-up sophomore album was recorded, following the untimely passing in 2001 of Warp’s co-founder Rob Mitchell from cancer at the age of 38, Steve Beckett was apparently not so keen on Plone staying with the label, and the band was promptly dropped from the roster, with the second LP remaining unreleased, although luckily enough for anyone curious enough to want to explore it, it can still be found on P2P file sharing services as well as on YouTube.

All of this proved to be a devastating blow to Plone, with the respective band members going their separate ways, Bainbridge eventually playing in the live incarnation of Broadcast, Johnston releasing a few solo singles as Mike In Mono and joining ZX Spectrum Orchestra, and Cancellara to all intents and purposes abandoning any sort of career in music altogether. In the intervening years, however, Plone’s esteem among electronic music aficionados only grew, so it proved to be an entirely unexpected, but very welcome surprise when Plone, now reduced to a duo of Bainbridge and Johnston, made a return with the album Puzzlewood, a somewhat stylistically different and sonically more diverse offering, which was released in 2020 on the group’s rightful spiritual home of Ghost Box, the hauntology-indebted record label co-founded by the graphic designer Julian House, known among other works for Broadcast’s album sleeves, as well as his musical endeavors under the guise of The Focus Group, along with Jim Jupp, best known under the moniker of Belbury Poly.

The next, ninth tune, is served up by the long-running British instrumental outfit Red Snapper, which formed in London in 1993 around the core trio of Ali Friend on double bass, Richard Thair on drums and David Ayers on guitar joined across their assorted albums, EPs and singles by a rotating cast of guest musicians and vocalists. The group made their debut in 1994 with the almost eponymous Snapper EP issued by the short-lived Flaw Recordings operated by the equally no longer extant band The Aloof, which, as it happens, featured among its members Gary Burns and Jagz Kooner, formerly, along with the legendary producer and DJ Andrew Weatherall, of the one time Warp-signed trio The Sabres Of Paradise. Flaw also released Red Snapper’s two subsequent EPs, all three of which were later compiled in 1995 by Warp as a single release under the name Reeled And Skinned, the title of which alluded to the group’s edible fish-indebted name, thus marking the band’s debut on the label’s roster, with their first full-length album, entitled Prince Blimey arriving only a year later.

Red Snapper are known for having pioneered a particularly invigorating blend of both live and electronic instrumentation drawing on a wide variety of styles, ranging from hip-hop, through avant-garde jazz, dub, funk, and even all the way to post-punk, and it is through this diverse stylistic lens that their contribution to “WAP100” is perhaps best viewed. For simplicity’s sake, however, one may very well describe “4 Dead Monks,” which is included on the compilation in the form of an original demo, and would appear in completed, studio-polished version on Red Snapper’s sophomore album Making Bones released by Warp in September of 1998, as essentially instrumental trip-hop—that particularly British, not infrequently blunt-assisted take on American hip-hop, the origins of which can be traced back to the city of Bristol and the three world-renowned acts hailing from that English locale, namely Massive Attack, Tricky and Portishead—what with its head nodding friendly, driving hip-hop-indebted beat played on live drums, a propulsive bassline played on double bass, a blend of classical guitar-flavored and energetically strummed electric guitar melodies and a plethora of electronic flourishes.

Red Snapper would conclude its association with Warp with their third album, the whimsically-titled Our Aim Is To Satisfy Red Snapper, which the label released in the year 2000, whereupon the band signed with the venerable London-based institution Lo Recordings, and continues to be associated with that label to this very day, although at present the group has been reduced to a duo of Friend and Thair, albeit often augmented for the purpose of live gigs by a number of additional performers and singers.

“Umchunga Locks,” the 10th song on the compilation is the work of Mira Calix, the artistic alias of Chantal Passamonte, who was born and raised in South Africa, but moved to London, England in 1991, and begun her association with Warp Records in a rather unusual way, by serving as the label’s publicist from 1994 to 1997, and only making her debut as a recording artist with the 2-track vinyl-only 12’’ single Ilanga which Warp issued in 1996, and which according to the record’s credits was “assisted by Gescom,” which bears noting in that Gescom is an umbrella project helmed by Sean Booth and Rob Brown of Autechre, and comprised of a revolving cast of some 20 individuals, most of whom remain anonymous, but also among them are such known luminaries as Darrell Fitton (aka Bola), the noise musician Russell Haswell and Andy Maddocks, the founder of the legendary British independent label Skam Records, which has released most of Gescom’s output, and alongside Warp was instrumental throughout the course of the 1990s and the 2000s in promoting the sort of forward-thinking electronic music which has come to be commonly described as IDM. Mira Calix’s collaboration with Gescom is also notable for the fact that Passamonte was for a time married to Sean Booth, a union which may well be described with some degree of facetiousness as IDM’s first genuine “power couple.”

“I just think it’s really funny to have terms like that. It’s basically saying ‘this is intelligent and everything else is stupid.’ It’s really nasty to everyone else’s music. (laughs) It makes me laugh, things like that. I don’t use names. I just say that I like something or I don’t.” ~Aphex Twin (Regarding the IDM genre term)

Mira Calix released her full-length debut, entitled One On One, in the year 2000, and continued to be associated with Warp for the remainder of her artistic career, with her final, and arguably best album, Absent Origin arriving in 2021. Her music eludes simple stylistic classification, given that while most of her Warp releases were highly rhythmic in nature, taking in everything from frenetic IDM beats, through abstract, experimental audio collages, to the found-sound and field recording stylings of musique concrète, she also created music for installations and sound sculptures, and provided soundtracks for theatre and opera productions.

The one major through line present in the vast majority of Mira Calix’s work, however, is that there is something very primal, and dare one say primitive, in the best possible meaning of the term, as in the Art Brut tradition of unschooled creativity, and also a marked feminine spirit imbuing it all, a quality still sadly missing from the contemporary electronic scene, with female and non-binary producers representing but a fraction of the overall population of electronic music-makers, making the field decidedly something of a boys’ club. Indeed, at the time of her signing to Warp, Mira Calix was the only solo female electronic producer on the label, and unfortunately the fact of this singular distinction hasn’t been remedied with time, as she still remains the only such musician the label has had on its roster to this very day.

Back to the tune at hand, or perhaps ear, as things may be, Mira Calix’s contribution to We Are Reasonable People is at once minimalist in its bare-bones simplicity, and maximalist in the relentless, repetitive tribal pounding of its industrial-strength beats interspersed with a very basic xylophone-esque melody and looped snatches of Passamonte’s own voice, which occasionally break into a discernable vocal part intoning the lyrics “Everybody loves the sunshine,” which seem to stand at odds with the overall abrasiveness of the production aesthetic employed here, which is anything but “beach fun in the sun” in nature.

The reader may have noticed that Chantal Passamonte is being referred to here in the past tense, and it bears explaining to those yet unaware of the facts of the matter, that she is one of four Warp artists who made an appearance on the “WAP100” compilation who are sadly no longer with us, having tragically taken her own life in March of 2022 at the age of 52. As for the remaining two musicians which have not yet been mentioned, and who in the intervening years have departed this Earthly plane for the proverbial “great gig in the sky,” they shall be discussed shortly.

The penultimate track, “Circulation,” belongs to Two Lone Swordsmen, a duo, as their name clearly implies, of Andrew Weatherall and Keith Tenniswood, formed in 1995 following the dissolution in the same year of the aforementioned production trio The Sabres Of Paradise, of which Weatherall was a key member, and with whom he released three full length albums and a number of singles issued by Warp between 1993 and 1995. To anyone worth their salt and with even a passing interest in the field of dance music, Andrew Weatherall ought need little in the way of an introduction, but to those not entirely familiar with this giant in the field of DJ-ing and electronic music production, it may be worthwhile to bring up his considerable contributions as a record producer to Primal Scream’s acid house-meets-indie rock classic “Screamadelica,” as well as to the somewhat more slept-on favorites such as One Dove’s “Morning Dove White” and Beth Orton’s “Trailer Park.” He was also an incredibly prolific remixer, with his long list of credits including remixes of tracks by New Order, Björk, Manic Street Preachers, My Bloody Valentine, The Orb, The Future Sound Of London, and Happy Mondays among many others. His oftentimes marathon DJ sets, meanwhile, were legendary in their own right, and a fraction of that manic dancefloor energy one could experience at a club where Weatherall was behind the decks has been preserved in the mix CDs he released for such labels as Fabric, Force Tracks and Ministry Of Sound.

Weatherall’s work as part of The Sabres Of Paradise was a heady blend leftfield electronica, influenced by such wide-ranging styles as dub, downtempo, trip-hop, techno, progressive house and trance, and the initial output of his subsequent project Two Lone Swordsmen with recording, mastering and vinyl-cutting engineer, as well as producer and DJ in his own right, Keith Tenniswood, can be described in roughly similar terms, albeit with a with a slightly more minimalist bent, and incorporating elements of IDM and electro for good measure.

Towards the latter part of Two Lone Swordsmen’s career, however, they’ve branched out to also embrace new wave, alternative rock, and even rockabilly, although without entirely abandoning their arsenal of electronic production techniques and instrumentation. One might well say that much like the universe itself, Two Lone Swordsmen started with a bang, because their full-length debut, The Fifth Mission (Return To The Flightpath Estate), issued in 1996 on Weatherall’s own label Emissions Audio Output was a double album, a feat most artists accomplish much farther along in their career, if at all. Their sophomore LP, Stay Down, released in 1998, marked their Warp Records debut, and the duo went on to release a further two full-lengths, as well as a remix album, plus a number of EPs and singles with the label, before returning to the strictly independent path via Rotters Golf Club, a label operated in tandem by both Weatherall and Tenniswood, concluding their run of releases with another double album of a sort, albeit released in two separate installments, and titled Wrong Meeting and Wrong Meeting II, respectively.

In this respect, Two Lone Swordsmen’s contribution to “WAP100” is somewhat of an outlier in the TLS catalog, in that it is a very straightforward and largely unremarkable, which is by no means to say bad, four-on the-floor minimal techno banger with much in the way of repetition and little in the way of variation, but one which can serve as absolutely excellent DJ tool sure to get any dancefloor moving. In a great loss for the electronic music community, however, there will never be any more triumphant DJ sets nor studio audio emissions from Andrew Weatherall, as he sadly and unexpectedly passed away from a pulmonary embolism in February of 2020, aged 56, yet another legend gone too soon and far before their time.

We Are Reasonable People ends on a thumping high note, courtesy of Mark Bell, a producer best known as the founding member of LFO, an acronym for “Low Frequency Oscillation” and not to be mistaken under any circumstances with the identically monikered American boyband purveyors of hideous pop, whose deciphering of the letters LFO reads as “Lyte Funkie Ones.” The genuine article LFO, if one will, begun life in Leeds in 1988 as the brainchild of Mark Bell, Gez Varley and Martin Williams, releasing an eponymous debut three-track single on Warp in 1990, which would remain the project’s label home for the entire duration of its career, with the title track “LFO (The Leeds Warehouse Mix),” created in the mold of the distinctly English bleep techno subgenre, soon becoming a certified dancefloor classic, and proving that British electronic producers could easily hold their own when it came to modifying Detroit techno’s and New York electro’s blueprints to create new, exciting an uniquely British molds of dance music.

Martin Williams departed the group following the release of their breakout debut single, leaving Bell and Varley to soldier on as a duo, who made best of the circumstances with the aptly titled sophomore single We Are Back issued in June of 1991 in the lead-up to LFO’s full-length debut, entitled Frequencies, an album filled rather appropriately, given both the group’s name and the LP’s title, with plenty of low frequency heavy stompers regarded favorably upon its July 1991 release by critics, fans and casual clubgoers alike. It would take five years for a follow-up album, Advance, to materialize, a wait which may well have contributed to the departure of Gez Varley in 1996, the year of the sophomore LP’s release, on which a mere two tracks he co-produced with Bell appear, with the remaining ten all being Bell’s solo endeavors.

Varley went on to establish a solo career under the alias of G-Man, whilst Bell embarked on a fruitful collaboration with Björk, contributing production to a number of her albums, beginning with 1997’s Homogenic, and assumed the role of producer on Depeche Mode’s Exciter LP released in 2001. The final LFO album, and the sole full-length to be entirely helmed by Mark Bell alone, was called Sheath and arrived in 2003, although it is worth noting that he also has a solo LP entitled Surge created under the pseudonym Speed Jack to his credit, released in 1996 by the highly influential dance music label R & S.

Mark Bell’s contribution to the “WAP100” compilation, one of only three non-remix tracks in his discography to bear his name proper, has an intentionally rude, but rather amusing name of “A Salute To Those People Who Say Fuck You,” and as befits that title, is a harsh slice of hard techno featuring the sort of off-kilter melodies and distorted rhythms that were his stock-in-trade. It was by no means a bad move on Warp’s part to sequence the varied collection of tracks comprising We Are Reasonable People in such a way as to conclude it not with a whimper, but rather much in the way it also begins, which is to say with a bang, or perhaps more aptly, a banger, in the most literal sense of the term. A very melancholy coda must be added to Mark Bell’s biography recounted in this review, in that unfortunately, he is the fourth Warp artist appearing on this compilation to no longer be among us, having died in October of 2014 at the much too premature age of 43, following complications from surgery.

These may very well be the disgruntled grumblings of a Gen X-er born in the year 1980 when it comes to asserting that much of what is possible within the realm of electronic music has already been done, but there may well be some truth to that notion, in that a lot of contemporary electronic producers seem to be looking mainly backwards in time for inspiration, without necessarily bringing much new to the conversation, which is none more apparent than in Gen Z’s ongoing obsession with 1990s fashion, technology and of course music—whether it be that decade’s electronic explorations into jungle, breakcore, trip-hop, techno or even gabber—and while it most certainly had always been thus, as any one artist is by necessity influenced by music which came before them, and there is of course no rule mandating that a piece of music has to be innovative to be truly enjoyable. That having been said, however, it certainly does appear that those genuine “WOW!” moments of hearing something that sounds truly iconoclastic and revolutionary, building upon the glorious ruins of the past an edifice that whilst not entirely without precedent, nevertheless manages to bring a novel take on an already established sound, are increasingly becoming fewer and far between these days.

This writer will be the first to admit that this may be the inevitable hallmark of aging, having been an avid listener of music for several decades now, and of course since the heyday of IDM there have emerged wholly distinct strains of electronic music, such as dubstep or footwork, both of which Mike Paradinas’ (better known under his musical alias of µ-Ziq) Planet Mu imprint alongside Steve Goodman’s (aka Kode9) Hyperdub label, can take a large credit for popularizing to a wider audience, or the hyperpop aesthetic pioneered by the PC Music stable of artists such as the late and dearly missed SOPHIE (who, it bears noting, was greatly influenced by Autechre, whom returned the favor by remixing her Blipp single).

“It certainly does appear that those genuine “WOW!” moments of hearing something that sounds truly iconoclastic and revolutionary, building upon the glorious ruins of the past an edifice that whilst not entirely without precedent, nevertheless manages to bring a novel take on an already established sound, are increasingly becoming fewer and far between these days.” ~Roman W.

In the years and decades following the release of the “WAP100” compilation, Warp slowly but surely morphed into a very different entity, one no longer focused primarily on instrumental electronic music, branching out into such diverse genres as indie rock (Gravenhurst, Grizzly Bear), hip-hop (Beans, Danny Brown) alt. R&B (Kelela) and even contemporary classical (Kelly Moran), in the process becoming more or less yet another indie label powerhouse (think 4AD following the departure of its founder Ivo Watts Russell), one which still releases intriguing and noteworthy music, and whose legacy acts which helped to establish Warp as being at the forefront of cutting-edge sounds, such as Autechre, Aphex Twin, Boards Of Canada, Squarepusher and Plaid—all well represented on “WAP100″—still continue to release exciting albums stamped with the label’s logo, but it can’t be helped to note that subjectively speaking, many of their more contemporary signings don’t offer quite the same boundary-pushing thrills as had the case in the first decade or so of Warp’s existence.

Now, as to whether the fine folks at Warp are indeed reasonable, perhaps it’s best to leave that value judgment to its stable of artists, both past and present, but there is little doubt that there once was a time that the label was as equally weird as it was radical, and the compilation at hand, representative of a period many listeners perhaps rightfully regard as Warp’s “golden age,” while admittedly not without its flaws, is a solid proof of that claim.

Artwork by The Designers Republic

Mastering by Frank Arkwright

We Are Reasonable People is available on Warp. [Bandcamp] | Site]

*Note: This article was originally published on June 7th, with introductory revisions made on June 8th.

![Romanowitch :: A critical season substitute (glitch.cool) — [concise]](https://igloomag.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/romanowitch-a-critical-season-substitute_tape_feat-75x75.jpg)