![]() The last thing one would expect from a label with a name like 130701 is a catalog of primarily of post-classical and orchestral works, but this is indeed the label’s remit. A sub-division of Brighton-based UK label FatCat Records, 130701 was created to house under one umbrella all those modern classical and orchestral releases that FatCat wished to put out with a slightly different, more readily associated identity. The label was named after the date of its inception (13th July 2001) and since then has become the spiritual home of the hugely influential Max Richter and the playful Hauschka as well as releasing works from Sylvain Chauveau and Set Fire To Flames.

The last thing one would expect from a label with a name like 130701 is a catalog of primarily of post-classical and orchestral works, but this is indeed the label’s remit. A sub-division of Brighton-based UK label FatCat Records, 130701 was created to house under one umbrella all those modern classical and orchestral releases that FatCat wished to put out with a slightly different, more readily associated identity. The label was named after the date of its inception (13th July 2001) and since then has become the spiritual home of the hugely influential Max Richter and the playful Hauschka as well as releasing works from Sylvain Chauveau and Set Fire To Flames.

2011 has seen three releases from 130701 so far (with a re-issue of Dustin O’Halloran’s live recording Vorleben – originally issued in a limited run by Sonic Pieces last year – due in June) that provides us with equal parts emotion, invention and drama.

::…:…:…….::::…::..::::…..:::.:…….::::…::.:…….::::…:::…..:::.:…….:::

O’Halloran weaves breathtaking tapestries of delicately balanced piano, strings and subtle electronics, gently adding one colour at a time to create a collection of works that are both utterly heartbreaking and inspirational, their final images revealed in moments profound beauty.

It may not come as much of a surprise to those already familiar with O’Halloran’s previous work to discover that his ambitions have widened considerably as Lumiere finds him now applying his talent for painterly compositions and arrangements to larger ensembles, the credits for which are a veritable whose-who of familiar faces. Featuring strings performed by New York’s American Contemporary Music Ensemble (ACME) who have previously collaborated with stable-mates Max Richter and Hauschka as well as Grizzly Bear, Nico Muhly and Matmos, guitar from Stars of the Lid’s Adam Wiltzie, violin from the prolific Peter Broderick, mixing by none other than Johann Johannsson and Nils Frahm providing studio engineering skills in the studio, it’s an impressive list of post-classical peers.

O’Halloran’s work has always possessed a certain je ne s’ais quoi that frustrates attempts to adequately describe it in words and Lumiere is no exception. However, details of his background as well as the conception, composition and recording of the album provide some clues as to what this elusive element might be. Having lived and worked in LA, the lush countryside of rural Italy and latterly in Berlin, O’Halloran has soaked up a variety of distinctive atmospheres, environments and paces of life. It is his synaethesia – a condition that allows him to visualise his compositions as a painter might, in terms of colours, textures and layers – that O’Halloran says formed a major role in the creation of the album, translating these environments into musical forms.

And what spellbinding musical forms they are. It may be wise to have a handkerchief handy when putting Lumiere on, as you may not be able to survive the heartbreaking experience of “A Great Divide” without one. Opening the album with such an emotive composition is quite a system shock, the delicate chiming of what could be an assembled throng of carriage clocks introduces first cello, then violin, and in its closing minutes a distorted rumble of a distant thunderstorm so reminiscent of Johannsson’s “And in the endless pause there came the sound of bees” that carries the remaining instruments away. Fortunately, “Opus 44” then stretches its warm and comforting arms from the speakers and hugs the listener, offering relief and consolation.

Elsewhere there is a supreme lightness of touch, of understatement and congeniality that makes Lumiere sublimely easy to listen to but bewitchingly hard to relegate to the background. Take “Fragile N.4,” for example, a piece that could steal the scene of almost any great post-war period drama you can think of, carrying as it does an undercurrent of tragedy, loss and sadness only partly masked by an insouciance of spirit and brightness in outlook.

O’Halloran’s piano solos are also as arresting as usual, especially the drifting “Opus 55” as it arrives in soft velvet waves like the ripple of a vast, draped curtain (see the cover artwork with it blurry images of old cinema drapes onto which spectral, smoky text is projected for a visual metaphor). Only “Quintette N.1” seems to falter slightly, as if he were holding back in fear of overstatement. The build up from solo violin (presumably Broderick’s) through solo piano to full string quartet is exquisite, but never quite reaches the climax that could have provided full dramatic satisfaction.

O’Halloran weaves breathtaking tapestries of delicately balanced piano, strings and subtle electronics, gently adding one colour at a time to create a collection of works that are both utterly heartbreaking and inspirational, their final images revealed in moments profound beauty. That he does so without faltering, creating an experience every bit as magical and enchanting as his previous solo piano works should not raise any eyebrows. Dustin O’Halloran’s star is most definitely rising.

::…:…:…….::::…::..::::…..:::.:…….::::…::.:…….::::…:::…..:::.:…….:::

Hauschka :: Salon des Amateurs

A distinguished, classy, playful and eclectic mix of classical and dance influences, Salon des Amateurs is infused with the spirit of invention and represents some of Hauschka’s most enduring and memorable work to date.

There has been a considerable burst of activity from Volker Bertelmann’s Hauschka project over the last year or so. His last album, Foreign Landscapes, was released just last October, he has a forthcoming EP due this winter for Serein’s Seasons series, but right now we have the release of the flamboyant Salons des Amateurs. For those that don’t know, Hauschka’s speciality is the prepared and treated piano, which Bertelmann has used it to stunning effect on all previous album releases. Ping-pong balls, bottle tops, gaffa-tape, aluminium foil, even vibrators (don’t even ask) are placed across piano strings and hammers to create a cornucopia of different sounds, timbres and often unpredictable cadences that allow Bertelmann to become a veritable one-man band.

Much like O’Halloran on Lumiere, Hauschka has expanded his frames of reference and sonic template once again to incorporate not just orchestral arrangements (as heard on the far more sedate “Foregin Landscapes”) but drum-kits as well, and Salon des Amateurs emerges as a Hauschka release unlike any other. Named after the bar/club in Dusseldorf at which he hosts an annual piano festival, Salon des Amateurs is themed around a night out around the salon, but this time Bertelmann is channelling the whole Cologne electronic movement of the nineties, specifically Kompakt’s output at that time. What is remarkable, given the largely acoustic nature of this production, is just how clearly that inspiration shines in the final product. “Radar” shows this off immediately, the warm ambient dub bursts and stabs of horns beautifully complimenting Bertelmann’s rainbow of treated piano timbres but most importantly, a supple and well rounded thumping low end.

The bounce and roll of the cheerfully trundling “TwoAM” with its tingly harpsichord twangs, jittery percussion and dry clinking, or the wavy syncopation and rattling kettle-drum percussion of “Girls” both possess an unmistakably relentless “bumpa bumpa bumpa” rhythm and motion, bouncy bass tones and busy urban soundscape: this is exactly how a Thomas Fehlmann “Unplugged” could sound. The pieces are beautifully enhanced by cello work from Calexico’s Joe Burns, adding a wonderfully fresh, live jazz feel to the work. No matter where you are or what time it is, these tracks transport you to an airy lounge bar on a summer afternoon, doors and windows thrown open as the music plays.

Hauschka’s previous records have always been imbued with the feeling of motion, of traveling and of being propelled or transported somewhere, conjuring images of the trains, the railways, the metropolitan architecture of the 1930s (all fully supported by the accompanying art deco artwork) and though Salon des Amateurs is more cosmo than metro, these features are still prominent – the album resides within a sleeve featuring a print entitled “Trains and Boats and Planes” by Stefan Kurten. “Subsconscious” clearly has somewhere to be, and needs to be there fast, accordions lending a Parisian flavour to the journey, whilst the brass and relentless momentum of “TaxiTaxi” evokes images of mechanised cities like the Paris of Jacques Tati’s “Playtime”. The piano is barely recognisable in “Cube” so radically altered are it’s inner workings, clonking, ticking, pinging and once again subtle electronic flourishes and accents further expand the soundstage.

A distinguished, classy, playful and eclectic mix of classical and dance influences, Salon des Amateurs is infused with the spirit of invention and represents some of Hauschka’s most enduring and memorable work to date, one that demands to be investigated by music lovers at both ends of the spectrum it so vigorously embraces.

::…:…:…….::::…::..::::…..:::.:…….::::…::.:…….::::…:::…..:::.:…….:::

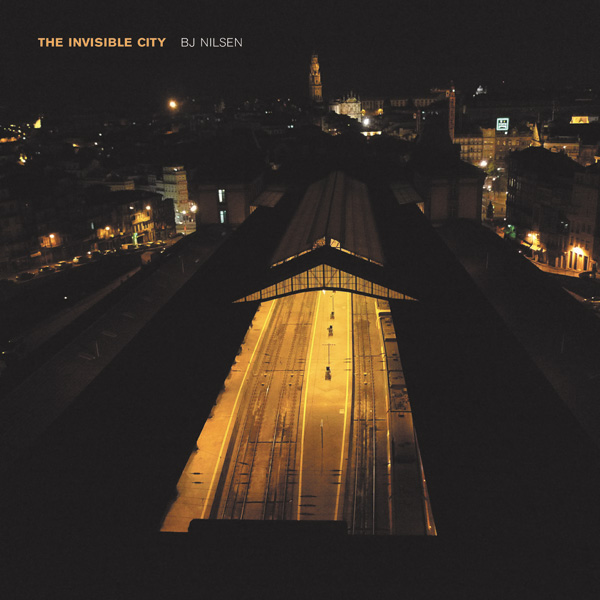

Johann Johannsson :: The Miners’ Hymns

As a soundtrack to a document of a way of life now extinguished, one that inflicted great hardship and turmoil, but that also brought communities so staunchly together, it is exceptionally uplifting and reverential.

Those familiar with Johannsson’s oeuvre will know that for some time now he has composed primarily for strings and orchestra, often for film and theatrical soundtracks, resulting in an eclectic style but with electronic flourishes and accents that are quite recognizably his. The Miners’ Hymns is yet another soundtrack from the artist, the result of a collaboration between Johannsson and American experimental filmmaker Bill Morrison, originally presented as a live performance at Durham Cathedral across two nights in July 2010 and commissioned for the civic-sponsored Brass: Durham International Festival that incorporates the Miner’s Gala, celebrating the culture of mining and the strong regional tradition of brass bands.

The result is Morrison’s film that employs archival footage from the BFI, BBC and Yorkshire Films to celebrate the social, cultural and turbulent political aspects of the now extinct coal mining industry, and Johannsson’s stunning soundtrack performed and recorded live in Durham Cathedral featuring a specially assembled sixteen-piece brass ensemble including members of the NASUWT Riverside band, originally formed in 1877 as The Pelton Fell Colliery Band, and the cathedral’s own organ played by Robert Houssart. That’s a fair amount of baggage and history for a project like this to be carrying, but if anyone can pull it off, Johannsson surely can.

“They Being Dead Yet Speaketh” opens the album with supple, warm and rounded organ chords that flare and decay as if transmitted to the viewer like the beam of light from a distant lighthouse, a cool drone’s presence felt in the ether. This builds over the course of five minutes first with additional brass instruments and then with rolling kettle-drums and finally thunderous percussion. It’s a majestic opening to The Miners’ Hymns, a heartfelt piece that speaks of tragedy and loss ultimately tinged with hope. “An Injury To One Is The Concern Of All” is a far darker affair, a cavernous but strangely lacking in low end rumble on the edge of hearing creates an unearthly ambiance, and atonal brass takes second stage to an increasingly violent onslaught of thunder until it joins the throng in surging waves. It is deeply harrowing, and perfect soundtrack material.

The Miners’ Hymns‘s shorter tracks, such as the stoic and determined “There Is No Safe Side But the Side of Truth” or “Industrial and Provident, We Unite to Assist Each Other” are more obviously narrative, once again appropriately titled with real slogans from the era, but it’s debatable whether all of this truly works as a standalone album. Much of it appears to be a rather literal translation of the images beamed onto the screen by Bill Morrisson, or simply doesn’t have the necessary cohesion or power to make an impact fully without those images. Taken in conjunction with the archival footage of processions, parades, protests, riots, the claustrophobic and dangerous mine shafts and the sheer array of faces – smiling, angry, exhausted, determined – however, it is deeply moving.

The Miners’ Hymns is quite a departure for Johannsson, the first time he has composed primarily for brass and though lacks some of his trademark subtlety as a result that is probably missing the point. As a soundtrack to a document of a way of life now extinguished, one that inflicted great hardship and turmoil, but that also brought communities so staunchly together, it is exceptionally uplifting and reverential. Like a soundtrack for Dziga Vertov’s “Man With A Movie Camera” or Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin, this particular work is undoubtedly best experienced alongside the movie and it is therefore recommended that you pick up the version that comes with Morrison’s film for the fullest experience.

::…:…:…….::::…::..::::…..:::.:…….::::…::.:…….::::…:::…..:::.:…….:::

All releases above are out now on 130701.

![Romanowitch :: A critical season substitute (glitch.cool) — [concise]](https://igloomag.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/romanowitch-a-critical-season-substitute_tape_feat-75x75.jpg)